Catherine Hockmuth, UC San Diego

Nanoengineers at the University of California, San Diego have developed a 3-D-printed device inspired by the liver to remove dangerous toxins from the blood.

The device, which is designed to be used outside the body — much like dialysis — uses nanoparticles to trap pore-forming toxins that can damage cellular membranes and are a key factor in illnesses that result from animal bites and stings, and bacterial infections. Their findings were published May 8 in the journal Nature Communications.

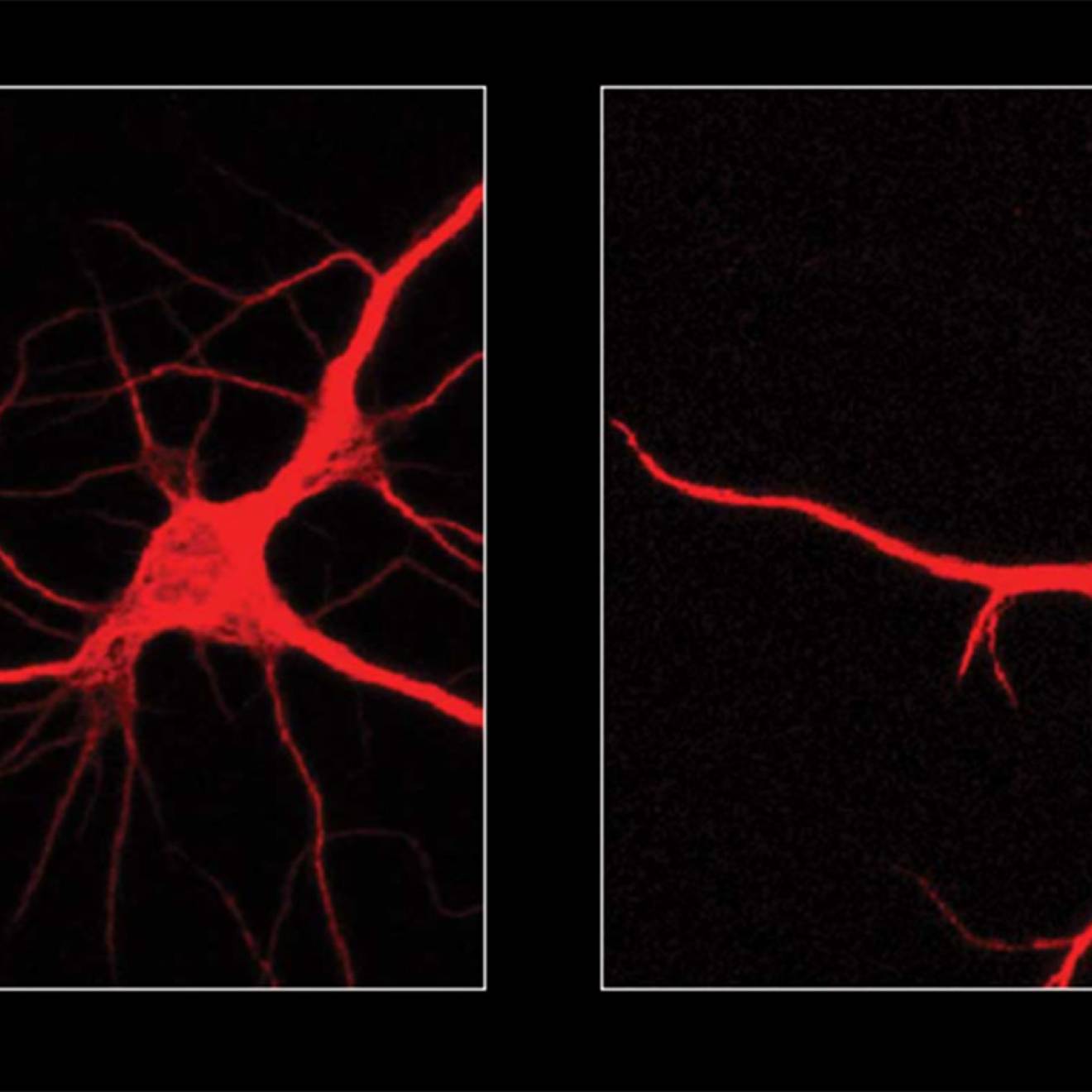

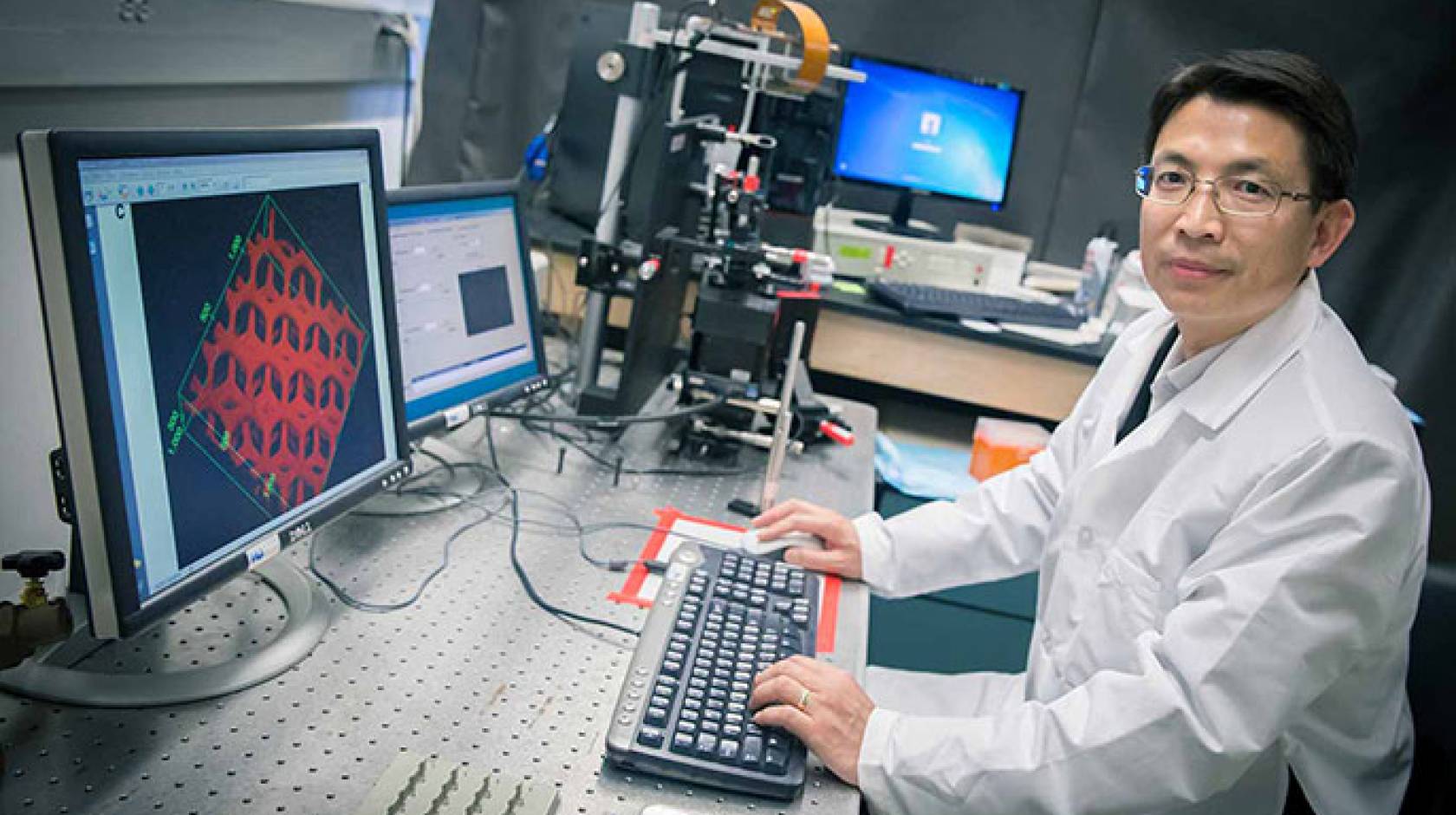

Nanoparticles have already been shown to be effective at neutralizing pore-forming toxins in the blood, but if those nanoparticles cannot be effectively digested, they can accumulate in the liver creating a risk of secondary poisoning, especially among patients who are already at risk of liver failure. To solve this problem, a research team led by nanoengineering professor Shaochen Chen created a 3-D-printed hydrogel matrix to house nanoparticles, forming a device that mimics the function of the liver by sensing, attracting and capturing toxins routed from the blood. The device, which is in the proof-of-concept stage, mimics the structure of the liver but has a larger surface area designed to efficiently attract and trap toxins within the device. In an in vitro study, the device completely neutralized pore-forming toxins.

“One unique feature of this device is that it turns red when the toxins are captured,” said the co-first author, Xin Qu, who is a postdoctoral researcher working in Chen’s laboratory. “The concept of using 3-D printing to encapsulate functional nanoparticles in a biocompatible hydrogel is novel,” said Chen. “This will inspire many new designs for detoxification techniques since 3D printing allows user-specific or site-specific manufacturing of highly functional products,” Chen said.

Chen’s lab has already demonstrated the ability to print complex 3-D microstructures, such as blood vessels, in mere seconds out of soft biocompatible hydrogels that contain living cells.

Chen’s biofabrication technology, called dynamic optical projection stereolithography (DOPsL), can produce the micro- and nanoscale resolution required to print tissues that mimic nature’s fine-grained details, including blood vessels, which are essential for distributing nutrients and oxygen throughout the body. The biofabrication technique uses a computer projection system and precisely controlled micromirrors to shine light on a selected area of a solution containing photo-sensitive biopolymers and cells. This photo-induced solidification process forms one layer of solid structure at a time, but in a continuous fashion.

The technology is part of a new biofabrication technology that Chen is developing under a four-year,$1.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01EB012597). The project is also supported in part by a grant (CMMI-1120795) from the National Science Foundation.