Ivan Natividad, UC Berkeley

Michelle Maxwell got her acceptance letter to UC Berkeley while on parole and living in a San Leandro halfway house.

Maxwell had served over eight years for robbery, but took advantage of that time by taking community college courses and earning three associate’s degrees. She applied to Berkeley while still incarcerated in a Stockton jail cell, hoping to get in and prove she was more than her past convictions.

It would give her a fresh start.

“When I found out, I cried and called my mom right away,” said Maxwell, who is now a second-year legal studies major. “I was so happy. All that hard work and discipline really paid off. I felt like it was an opportunity to start over again.”

But when Maxwell was released, just months before she was slated to begin at UC Berkeley, state law dictated that she stay 500 miles away, in San Diego County, where she had committed her last crime.

To attend UC Berkeley, she agreed to live in a rule-bound halfway house in San Leandro that supported parolees with a history of substance abuse. The problem? Maxwell didn’t have a substance abuse problem, and she would have to do things most of her fellow students didn’t.

A strict curfew made late-night study sessions impossible. Travel to and from San Leandro — sometimes an hour-long drive — could otherwise be spent meeting with friends or professors. And Maxwell was required to attend group addiction counseling, even though she didn’t need it.

“I was restricted all over again,” she said. “It didn’t feel like I was truly free to take in Berkeley the way I wanted to.”

Maxwell’s experience was not much different from many formerly incarcerated students attending UC Berkeley. But that changed last fall, when the state passed California Senate Bill 990, legislation that streamlines transfer and travel requests for California parolees to go to school, work and build new lives in areas outside of the county they were paroled to.

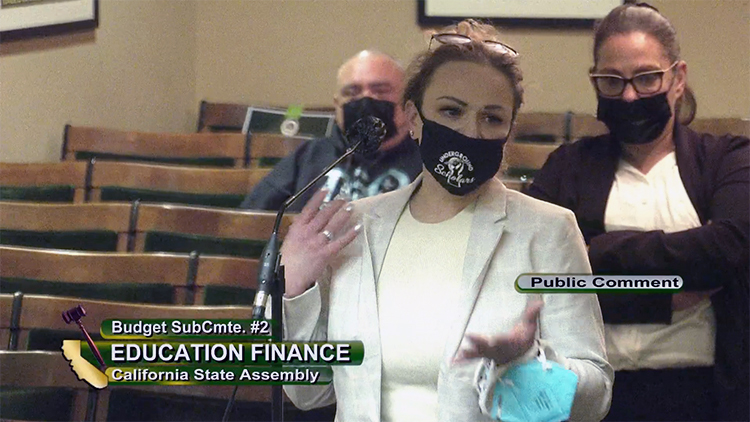

The bill became law in large part because of advocacy from formerly incarcerated students and policy fellows at Berkeley’s Underground Scholars Initiative (USI). Working with California State Sen. Ben Hueso, Maxwell and other Berkeley USI students sat through legislative sessions and wrote to and spoke with state representatives about the educational barriers they faced when trying to transfer their supervision to Alameda County after being accepted to UC Berkeley.

Michelle Maxwell

Barriers, Maxwell said, she is proud to have helped eliminate for future students.

“It is really empowering,” said Maxwell, who now lives just three blocks from campus. “Knowing how indifferent our lives and accomplishments as formerly incarcerated students can be perceived within this system, and to see our hard work come to fruition makes me excited for what more is to come.”

That legislative win is one of many that USI has won over the years through the group’s year-long policy fellowship, created in 2019 by USI Executive Director Azadeh Zohrabi, and in partnership with the Legal Services for Prisoners with Children.

Through the fellowship, formerly incarcerated students receive training in policy advocacy and statewide campaigns. Traveling to the state capitol, the students are given an opportunity to learn the ins and outs of how legislation is passed, while also building connections and sharing their stories with state legislators.

Those relationships have also garnered $4 million in ongoing funding from the state to expand staffing and resources for Underground Scholars student groups across the UC system.

“This gives us more capacity to focus on and engage in policy work even more than before,” said Zohrabi. “Work that can contribute to the implementation of prison-to-college pipeline programs that will make higher education more accessible and inclusive for our student community.”

Roots in advocacy

Ruben Lizardo, UC Berkeley’s local government and community relations director, has advised USI on policy throughout the years and said that policy advocacy has been in the group’s DNA since its inception. In 2013, when there were just a handful of students in the group, USI leaders campaigned to make Berkeley and other UC campuses more accessible and safer for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated students. In response, in 2014 Berkeley students voted for a fee referendum that provided funding to create a space for the USI program on campus.

In 2016, USI partnered with then-State Sen. Loni Hancock to include an allocation in the state budget to fund and develop Berkeley Underground Scholars, an academic support group on campus within USI for formerly incarcerated students and those affected by mass incarceration.

A year later, the student group also helped to “Ban the Box” on UC employment applications to make sure applicants were not discriminated against due to past criminal history.

“USI’s roots have always been in advocacy and taking action to make the lives of students on campus better,” said Lizardo. “They have pushed for resources and funding that had been necessary for years. And they continually strive to make Berkeley a more inclusive campus.”

UC Berkeley USI fellows and students, from left to right: Michael Garcia, Michelle Maxwell, Erin McCall and Kevin McCarthy.

While these campaigns were huge wins for USI, Lizardo said, it wasn’t until Zohrabi came to campus in 2018 that the legislative efforts were taken to another level.

Through the USI policy fellowship, Zohrabi has transformed the way the group approaches policy advocacy by providing weekly in-depth workshops and training on how the state legislative process works. Topics include: How many votes are needed to pass a bill? How do you work with opposition and address their concerns? How do you connect and communicate with representatives from the state? And what do you do when a state senator is not in agreement with the legislation you are backing?

That detailed approach to policy work has since led to a series of successful policy campaigns that include early parole release for students who complete college and other educational programs, a Ban the Box on all California college applications, and the campaign to pass Proposition 17 to restore voting rights to people on parole.

The USI also helped in the successful campaign to oppose Proposition 20, which would have rolled back key criminal justice reforms and returned to a ‘tough on crime’ approach to public safety.

“Azadeh brings the knowledge, experience and political savvy that is needed to run successful policy campaigns,” said Lizardo. “And she imparts to USI’s leaders tangible tools they need to empower other students to advocate for themselves and the communities they come from.”

Pulling strength from struggle

For Zohrabi, her role and work with UC Berkeley’s USI program also comes from a very personal place.

As an immigrant from Iran, Zohrabi said she has been impacted by incarceration her entire life. She first experienced issues with the criminal justice system when her parents were arrested in 1982 for speaking out against the Islamic regime just a few years after the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Azadeh Zohrabi is the executive director of the Berkeley Underground Scholars.

“They continued fighting against the regime for a secular democratic Iran and were incarcerated a few months after I was born,” said Zohrabi. “As a child, seeing the injustice in that really had an impact on what I wanted to do with my life. I understood early on how families are negatively affected by a system that unjustly incarcerates people. And how that struggle can impact an entire community.”

After immigrating to the United States as an adolescent, Zohrabi soon found parallels between what happened to her parents in Iran and the unjust incarceration that her friends, and her partner, experienced in America.

Finding purpose in wanting to change that system, Zohrabi earned a law degree from UC Hastings and threw herself into human rights work and advocacy, specifically for communities impacted by mass incarceration. She has served as a leader and director for notable Bay Area nonprofits such as the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights and Legal Services for Prisoners with Children (LSPC).

The USI’s policy fellowship began as a collaboration with LSPC to connect Berkeley students to the nonprofit’s resources and coalitions fighting to change policy that impacts formerly incarcerated students, in particular. Zohrabi said USI has expanded the fellowship opportunity to students outside of Berkeley and the 2023 cohort will include members of other UC campuses.

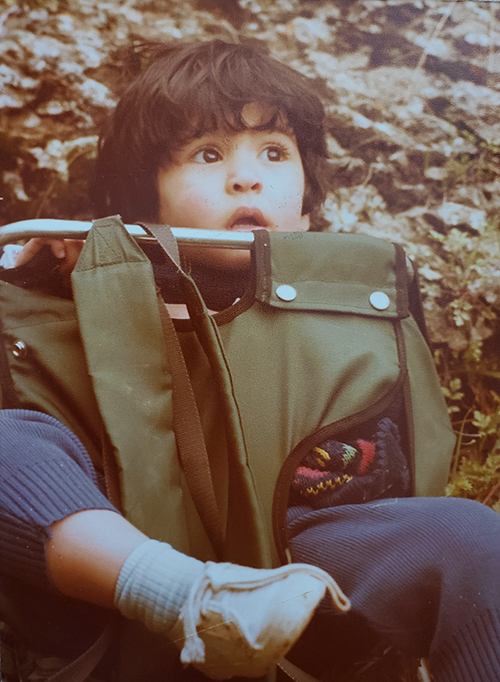

Zohrabi as a toddler, after her mother was released in Tehran from Evin Prison, and before they escaped from Iran.

“I am passionate about working with these communities because I believe that the work that we are doing is creating the condition of possibility for a radically different world to exist,” she said. “And being a part of [USI] has really transformed my life and given me the opportunity to have a huge impact on issues — that have also impacted me — and that I care about.”

That impact is evident for USI retention chair and policy fellow Erin McCall, who, this year authored a policy brief — along with four other Underground Scholars — released in UC Berkeley’s Institute for Research on Labor Employment that promotes career opportunities for formerly incarcerated firefighters. Her work with the policy fellowship “enabled me to see the direct connection between original research and the implementation of policy change,” said McCall.

“Azadeh is an inspiring mentor, and I couldn’t be more grateful for her leadership,” she said. “Traveling to Sacramento with the policy fellows this spring was empowering. Working together as a team to advocate for recurring funding made me feel like I was contributing to something bigger and far more important than myself.”

Seeing the bigger picture

Danny Muñoz, a former gang member, came to UC Berkeley after being in and out of the criminal justice system for over three decades. Now, as a youth mentor in the East Bay, he uses his life experiences to uplift the communities he came from.

Muñoz said USI’s policy fellowship has given him a greater perspective on the systemic inequities that cause under-resourced communities and schools to become pipelines to prison.

A sociology major, Muñoz is currently working on research based around the experience of middle school students and whether wealth plays a part on the interactions they have with adults at their schools. Working with Zohrabi, Muñoz said, has given him the confidence to tackle prejudiced policy and speak to high-level legislators about challenging issues.

“Being a part of this fellowship really opened my eyes to what is possible,” said Muñoz, who is also minoring in public policy and will graduate this spring. “I always felt like I could only make an impact with individuals, only working in my community where I come from. But having a hand in shifting policy, you see the bigger picture.”

For Zohrabi, that bigger picture starts with providing USI students with the resources to realize that they can be the decision-makers and leaders in policy, and that their voices “bring great value to a system that often ignores them,” she said.

“[Azadeh] is just a powerful female force,” said Maxwell. “She really knows her stuff. And that inspires all of us to treat these campaigns with urgency, because we know how important these policies are — not just to us, but to campuses around the entire state.”

Zohrabi with other USI allies and advocates in Sacramento.