Edward Lempinen, UC Berkeley

Americans are deeply divided over the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and it’s widely assumed the split reflects our bitter partisan conflicts. But a new study co-authored at UC Berkeley suggests one source of division stronger than any other: racial resentment.

White people who perceive that Black people use race to gain unfair advantages, and resent it, were far more likely to question the need for the bipartisan U.S. House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack, according to the study co-authored by David C. Wilson, dean at the Goldman School of Public Policy.

“Partisan politics are only part of the story when it comes to accountability for the events of January 6th,” Wilson said in an interview. “There is a strong racial component that is not only about prejudice but, more importantly, about how African Americans advance change and challenge status quo systems of merit.”

The distinction between racial prejudice and the contemporary dynamics of racial resentment is crucial in the research of Wilson and co-author Darren W. Davis, a political scientist at Notre Dame University. Many white people perceive that people of color are advancing unfairly, and their resentment is an emotional response to perceived injustice, the authors write. And that, they conclude, is likely the “dominant explanation” for why many think the insurrection was justified and needed no investigation.

In their analysis, the resentment syncs with support for former President Donald Trump and a message at the core of his Make American Great Again (MAGA) movement: that white people are unfairly losing out to groups that are getting advantages that they haven’t earned and don’t deserve.

In that sense, the co-authors wrote, the “Stop the Steal” slogan “used in billboards and placards to promote the theory of election fraud, was also a metaphor for what was at stake for the country.”

The paper — “Stop the Steal”: Racial Resentment, Affective Partisanship, and Investigating the January 6th Insurrection — is published in the latest issue of The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science.

Davis and Wilson, both professors and specialists in political psychology, are the authors of the 2022 book, Racial Resentment in the Political Mind (University of Chicago Press). In that volume, they argued that modern political divisions that are implicitly or explicitly racial are not solely about white racism. They repeatedly find that racial resentment inflames social and political conflicts that center on fairness, even when the issues have no obvious connection to race.

The new research focuses that lens tightly on the aftermath of the 2020 presidential election, won by Democrat Joe Biden, but still fiercely contested by Trump and millions of right-wing Republicans who comprise much of the MAGA movement.

In the flashpoint of Jan. 6, a culmination of U.S. racial history

Since the mid-20th century, landmark civil rights law and policy have given more political and economic power to Black people and other people of color, as well as to women, LGBTQIA+ people and others long marginalized by society. In the same span, the nation has become more racially and ethnically diverse.

A number of factors fueled white resentment, including the election of Barack Obama as the nation’s first Black president, and that sense of dislocation and loss has been further aggravated by economic instability, the COVID pandemic and global geopolitical tensions, Wilson said.

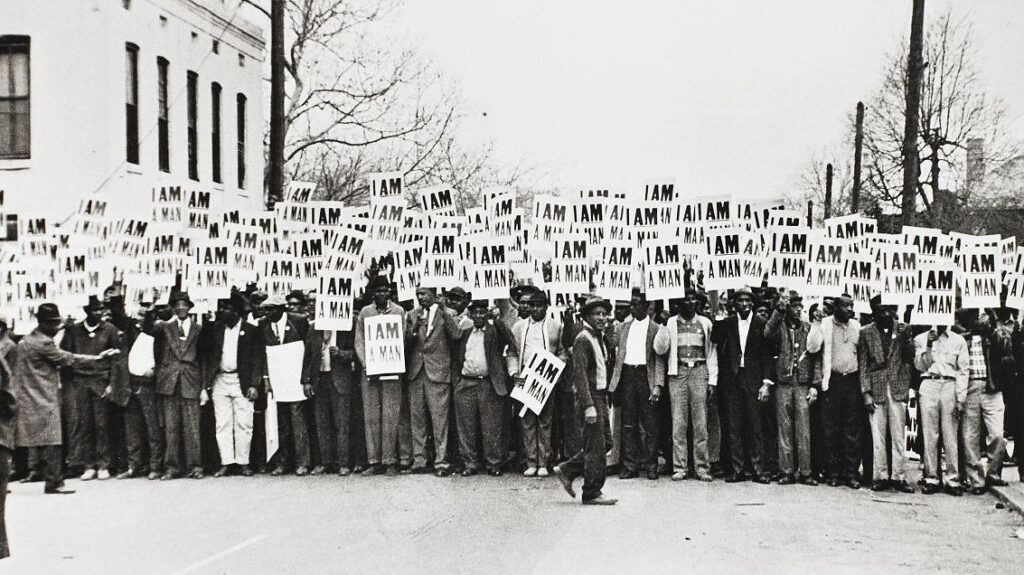

Ernest Withers via St. Lawrence University Art Gallery / Flickr

Racial resentment “is about how race disrupts the status quo for people and leads them to believe that they will be morally wronged because of race,” Wilson explained. “African Americans and other minorities have lived with this for the entirety of U.S. history, prompting a great deal of resentment toward whites who refuse to acknowledge structural unfairness or adoption of legitimate actions that restore justice.

“What most whites are thinking about now is, ‘OK, racism is bad, and I don’t dislike Blacks, but what do these demands for change mean for me, my family and my ability to live a good life?’ They become very protective of what they have, what they know and how they behave. They don’t want change that truly equalizes opportunity in society, they want change that helps Blacks, but at no expense to them.”

Biden won the 2020 election by some 7 million votes, but that masked how tight the contest was in battleground states such as Georgia, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Arizona. A relative handful of votes in those states could have tipped the Electoral College to Trump.

In the aftermath of the election, Wilson and Davis write, racial considerations were woven throughout efforts by Trump and his allies to overturn the results.

Their fraud charges centered on Black-majority cities such as Atlanta, Philadelphia, Detroit and Milwaukee, claiming with no evidence that those cities had deprived him of victory. They viciously criticized two Black poll workers in Georgia, falsely accusing them of perpetrating a massive fraud.

Racial themes were pervasive in the Jan. 6 insurrection itself, Wilson said. White supremacy groups openly displayed their insignias. Some in the mob yelled racial slurs at the Capitol Police. News photographs showed a Civil War-era Confederate flag being carried through the Capitol.

“Many individuals and groups, spurred on by President Trump and his advisors, descended on the Capitol as a clarion call to the beginning of a race war,” the authors wrote.

Why didn’t Jan. 6 investigators focus on issues of race?

From the start, congressional efforts to investigate the insurrection were riven by partisan polarization. Republicans in the U.S. Senate blocked a bipartisan investigation. When the House formed its high-profile investigative panel, only two Republicans — both MAGA critics — agreed to serve.

Curiously, Wilson said, the House panel never closely assessed the racial dynamics underlying “Stop the Steal” and the attack on the Capitol. Just as the national discussion has focused on the warfare of Republican vs. Democrat, so too did the panel.

And yet, the authors suggested, such a narrow focus left a powerful driver of the insurrection largely unexamined.

“While the racial anxieties have received little attention in the explanation of the January 6th insurrection and investigation,” they wrote, “racial motivations could rival (or even overpower) partisan explanations.”

To understand our political divide, understand our racial divide

In their study, the researchers surveyed a number of public opinion polls to find that the American public was, on average, evenly divided in its attitudes about the House investigation. It’s no surprise that most Democrats favored it, and most Republicans opposed it.

However, Davis and Wilson argue, the data also show a racial split: “While whites are overwhelmingly opposed to a January 6th investigation, African Americans are overwhelmingly supportive.”

To understand why, the authors collected and analyzed data from a national survey of adults from the Cooperative Election Study conducted by YouGov and used that data to develop four analytic models for assessing opinions about the House Jan. 6 panel.

To be sure, Davis and Wilson found that “affective partisanship” — the life-and-death, us-vs.-them quality of today’s partisan warfare — had a strong bearing on how Americans viewed the House investigation. But racial prejudice toward Blacks was virtually “irrelevant” in shaping opinions about that probe, they wrote. Instead, they found that racial resentment has a far greater force.

The authors then analyzed the extent to which racial resentment affected the gaps between how people feel about Democrats compared to Republicans— and found that racial resentment is a powerful underlying force in polarization.

There’s so much overlap now between race and party identity “that they’re almost indistinguishable,” Wilson said in the interview. “If you look at most social science research, the strongest predictor of partisan identity is racial attitudes.

“If you make that argument, people might say, ‘You mean, because I’m a Republican, I’m racist?’ Well, no, they’re not racist. It means that when you think about race being used to advance political change in society, it activates fairness concerns that motivate you to scrutinize and question the efforts of racial-ethnic minorities in ways that you would not for whites or Republicans.”

“In this view,” the authors write, “whites’ grip over American society and the status quo is being threatened by African Americans and other minorities, immigrants, and counter-cultural groups (e.g., feminists and LGBTQ individuals). Exacerbated by racial stereotypes and misinformation that minorities are benefiting at their expense, many whites come to believe that such groups are skirting the rules of the game and violating values of fairness and justice.”

Inaccurate allegations of racism can deepen social division

An accumulation of such grievances has fueled the rise and persistent strength of Trump’s MAGA movement, they suggest.

“Many of President Trump’s supporters believed they were being victimized by election fraud in the 2020 election,” the authors wrote, “but they also believed that whites were being victimized more generally — the American way of life for them was changing and they were being disadvantaged by African Americans and other minorities. To them, the January 6th insurrection was about invalidating the 2020 election in order to retain President Trump for a second term and protect and defend that status quo.”

Given the volatility of the issue, Wilson cautioned against making broad accusations of racism, and against failing to understand the nature of racial resentment.

Most policy and political discussions are anchored in historical ideas of racism, he said, and ‘racism’ may be the word we use reflexively when policy or cultural issues turn to racial conflict. But that raises enormous risk for continuing polarization — and it makes reconciliation more difficult.

“We shouldn’t treat race in a cheap way, just relying on the easiest explanation,” he said. “Sometimes there’s a sense that white people … dislike Blacks or they want to keep Blacks down. But no — it could be that they genuinely have a problem with a policy, or they like a particular candidate better, but they are not racist themselves.

“That may lead to some discomfort, because it’s a slippery slope to letting racism and fascism and everything that follows take over. But you also run the risk of the slippery slope if you call everybody a racist, and they’re not. They’ll stop listening to you.”

David C. Wilson, dean of the Goldman School of Public Policy