Cynthia L. Chamberlin, Seira Santizo Greenwood, David E. Hayes-Bautista and Adriana Valdez, UCLA Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture

Long before UCLA officially came into being in 1919, a steadfast advocate for education in Southern California helped lay the groundwork for Los Angeles’s first public institution of higher learning. A state legislator from 1880 to 1886, Reginaldo Francisco del Valle was instrumental in establishing the Branch State Normal School at Los Angeles, which opened in 1882. Twenty-seven years later, the assets of the Normal School were absorbed by the University of California, becoming its first Southern California campus, UCLA.

Reginaldo del Valle was born in 1854 in Los Angeles at his family’s adobe house, four years after California became part of the United States. He was the eldest son of Ygnacio del Valle (1808–1880) and Ysabel Varela del Valle (1836–1905). His father came to Alta California in 1825 from the Mexican state of Jalisco. At the time, Alta California was part of Mexico, so Ygnacio del Valle was simply a Mexican citizen moving from one part of the country to another. Ysabel Varela was born in California and therefore was also a Mexican citizen.

At the end of the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), however, Mexico ceded nearly half its territory to the United States, an area comprising the modern U.S. states of California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and parts of Colorado and Wyoming. By the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the war, all Mexican citizens who chose to remain in those areas — and most did — automatically became U.S. citizens. This territorial expansion and the discovery of gold brought hundreds of thousands of immigrants to California from 1848 on, the majority from the Eastern and Midwestern states of the U.S. Within just a few years, the laws, culture and society of California were radically transformed.

As a result, although his parents were not immigrants, Reginaldo del Valle lived an experience similar to over half the children born in California since 2001: that of a U.S.-born, English-speaking Latino with Spanish-speaking immigrant parents. He grew up bilingual and bicultural, at home in both Latino and Atlantic-American civil society.

The fight for bilingual California

Elected as a California state assemblyman from Los Angeles in 1879, del Valle began his freshman term in office at the start of 1880. The original State Constitution of 1849 had been abolished and a new one written during the previous legislative term, in 1879. Among other things, the new Constitution did away with the old Constitution’s requirement that “All laws, decrees, regulations and provisions, which from their nature require publication, shall be published in English and Spanish.” Instead, from now on, all government business was to be conducted entirely in English.

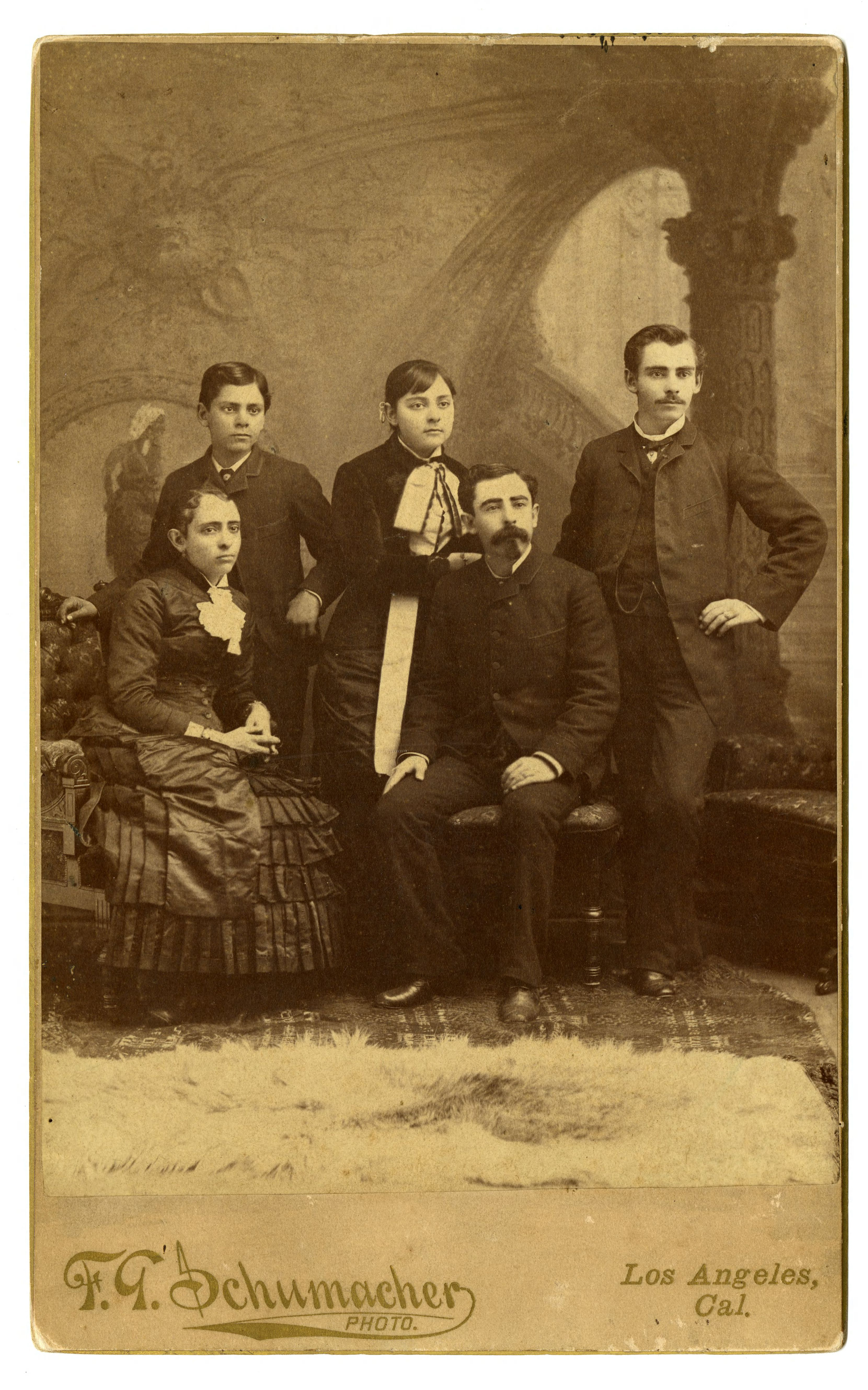

Reginaldo del Valle with his siblings. Left to right: Mrs. Josefa R. (del Valle) Forster, Ignacio del Valle, Jr., Mrs. Ysabel (de Valle) Cram, Reginaldo F. del Valle and Ulpiano F. del Valle, circa 1884–87

Among the first business taken up in the 1880 session were various bills meant to put this new English-only policy into effect, for example Assembly Bill (AB) 184, “An Act to Provide for the Keeping of Accounts in the English Language.” Opposed to the abolition of bilingualism in California’s government, del Valle tried to render the bill ineffective by amending it to strike out its enacting clause in AB 184. His motion, however, was voted down.

UCLA’s foundation

As a state assemblyman from 1880 to 1881 and then as a state Senator from 1882 to 1886, del Valle was largely responsible for the legislation establishing and funding the State Normal School at Los Angeles, as well as giving it an independent administration.

Early in 1880, a fire had destroyed the State Normal School (the publicly funded teachers’ training college) in San José. While that institution would be rebuilt, California’s legislature seized the opportunity to expand publicly funded higher education in the state. Barely two weeks after the fire, at the urging of former California Governor John G. Downey, del Valle introduced a bill to establish a Branch State Normal School in Los Angeles. He and Downey agreed that securing this institution would provide a much needed educational and economic boost for their community.

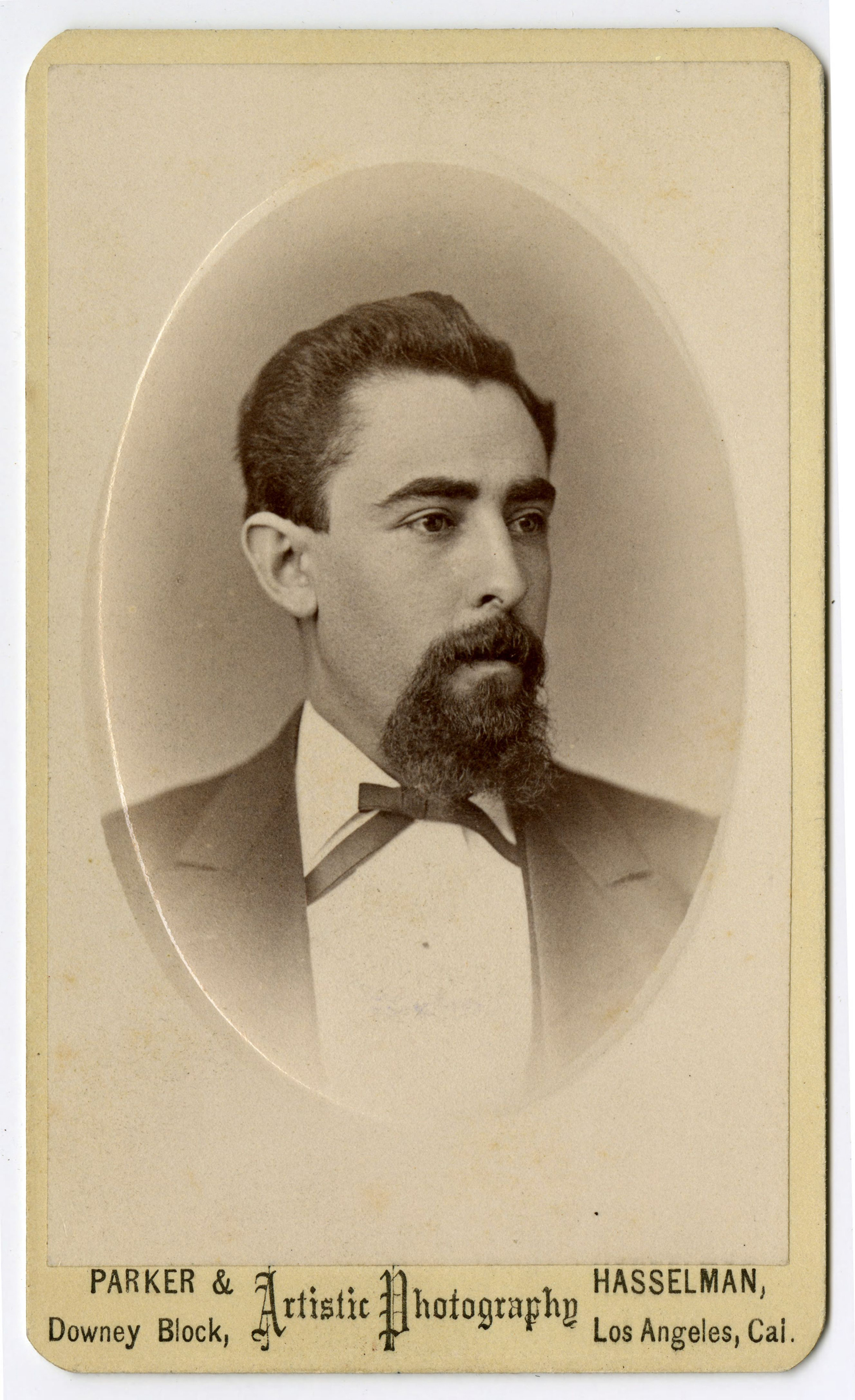

Reginaldo del Valle, circa 1878–80

Yet he was not the only legislator trying to secure such an institution for his community. Del Valle faced an uphill fight, for, at the time, most of the state’s population was concentrated in Northern California, and so were all of its public institutions. Still a young man in his mid-20s, del Valle was a good negotiator and a master of parliamentary strategy. When his own bill seeking to secure the Branch State Normal School for Los Angeles was defeated in the Assembly, he persuaded a fellow Angeleno colleague in the state Senate to introduce a virtually identical bill in that house. After the Senate passed that bill, del Valle then successfully guided it to approval in the Assembly.

On March 14, 1881, “An Act to Establish a Branch State Normal School” in Los Angeles was signed into law. At the opening ceremonies of the Los Angeles State Normal School the following year, del Valle proudly noted that this first state institution in Southern California was not “an asylum or a state prison, but a place where persons can be trained to teach our children.”

In 1919, the assets of the Los Angeles State Normal School were transferred to the Regents of the University of California. This provided the institutional platform on which the University of California, Los Angeles, was founded.

Not Spanish, but Mexican

After unsuccessful candidacies for a seat in the U.S. Congress in 1884 and for Lieutenant Governor of California in 1890, del Valle remained active in Democratic Party politics but did not seek political office again. Respected for his legislative skills, he was a lecturer on parliamentary law at the Southern California College of Law in 1892, and he practiced law for most of his life. Although many of his cases involved paying clients, he also represented some economically disadvantaged Latinos free of charge. His equal fluency in Spanish and English enabled him to understand and argue their cases effectively in the English-speaking legal system. The Latin Protective League recognized his pro bono legal work with an award in 1925.

Bilingual and bicultural, he was prominent in Southern California’s Atlantic-American society and a sought-after figure at social events, and at the same time belonged to many Latino organizations, such as La Junta Patriótica de Juárez, the Original Young Spanish Americans, and the Club Cura Hidalgo. He was a popular speaker at Cinco de Mayo and Mexican Independence Day celebrations and a source for historical societies and newspaper reporters interested in the real history of Latino California.

By the early 20th century, due to tremendous migration from the East Coast and Midwest, Atlantic-Americans had come to make up the majority of California’s population. These new arrivals knew little about the state’s history and for various reasons held romanticized notions about its 18th- and 19th-century past. They preferred to think of the Latino settlers of California before 1848 as “Spanish dons” — that is, people of white European descent like themselves — who used to lead carefree lives of fiestas and bullfighting.

On hearing such descriptions of “the good old Spanish days,” del Valle’s blunt response was “That’s a lot of bunk!” He objected when Atlantic-Americans referred to him or his ancestors as “Spanish,” and would explain that the Californios were Mexican, not Spanish. He was annoyed by the newcomers’ anglicized pronunciation of “Los Angeles,” and liked to demonstrate how it easy it was to say the Spanish name: “Just say Los Ang-hell-ess. Everybody ought to be able to do that.”

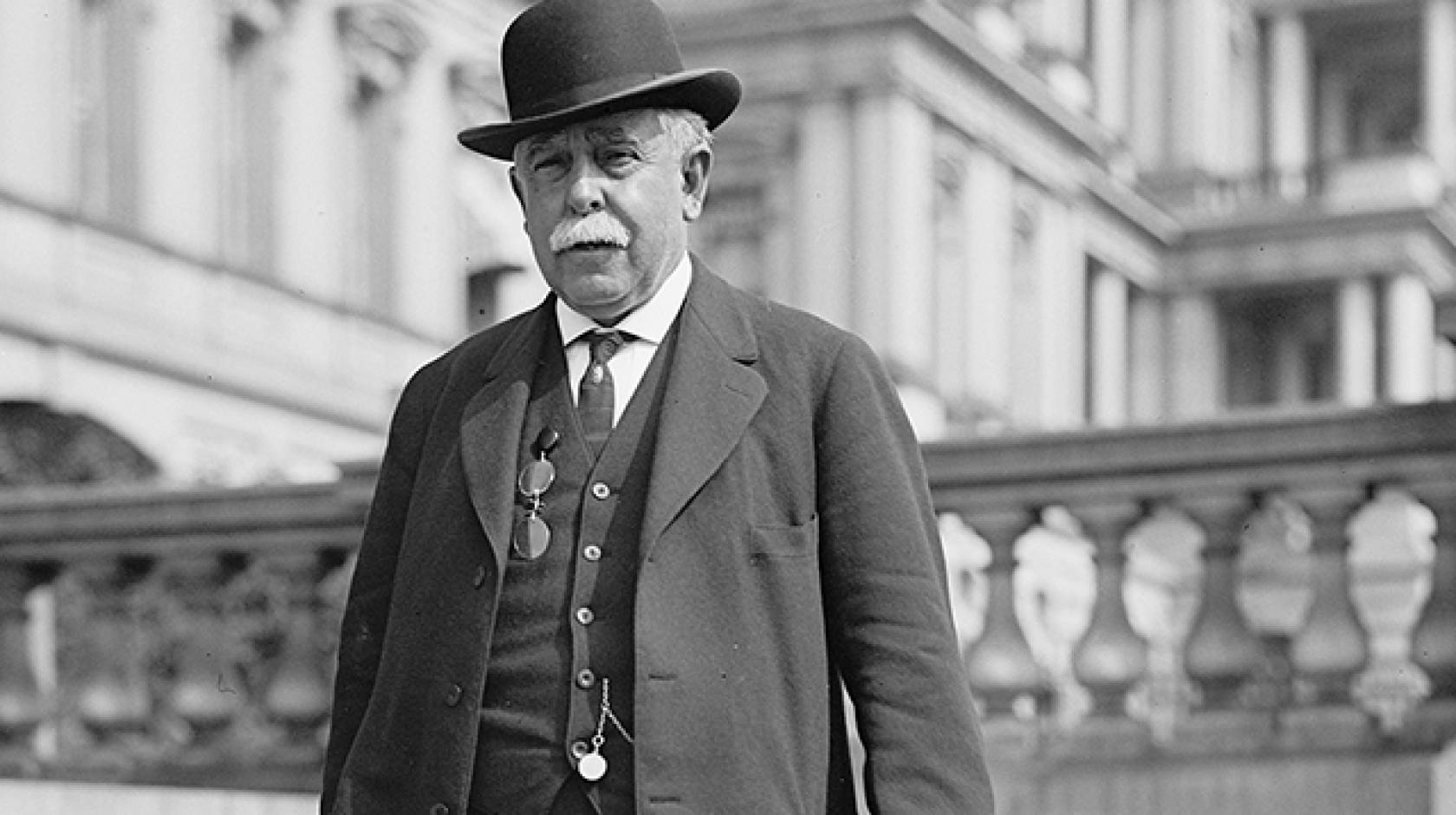

Reginaldo del Valle

Water to Los Angeles

The final important position del Valle held from 1908 to 1929 was on Los Angeles’s Public Service Commission, which was responsible for water, power, and other public services. It was the ancestor of today’s Department of Water and Power. Del Valle was president of the commission for much of that time, overseeing the Los Angeles Aqueduct’s chief engineer, William Mulholland, in the development of the water supply system that made possible the city’s exponential growth during the 20th century. During the Owens Valley water wars of the 1920s, when enraged ranchers seized and blew up the aqueduct that was diverting water from their lands to Los Angeles, del Valle used his political skills to broker a peace that allowed the aqueduct to be repaired and the project to go forward.

Although the Los Angeles Aqueduct was controversial, without it and other public infrastructure works undertaken during del Valle’s time on the Public Service Commission, Los Angeles never would have grown from a 19th-century frontier town into the metropolis it became during the 20th century. Del Valle was so influential in these developments that, just after his death, a memorial piece in the Los Angeles Times declared, “To him, as much as to anyone, Los Angeles owes the mighty aqueduct that was built to tap the water sources of the Sierra. His twenty-one years of service with the municipal agency responsible for our water and power development attest the esteem in which his fellow-citizens held him.”

Reginaldo del Valle in 1913