Robert Sanders, UC Berkeley

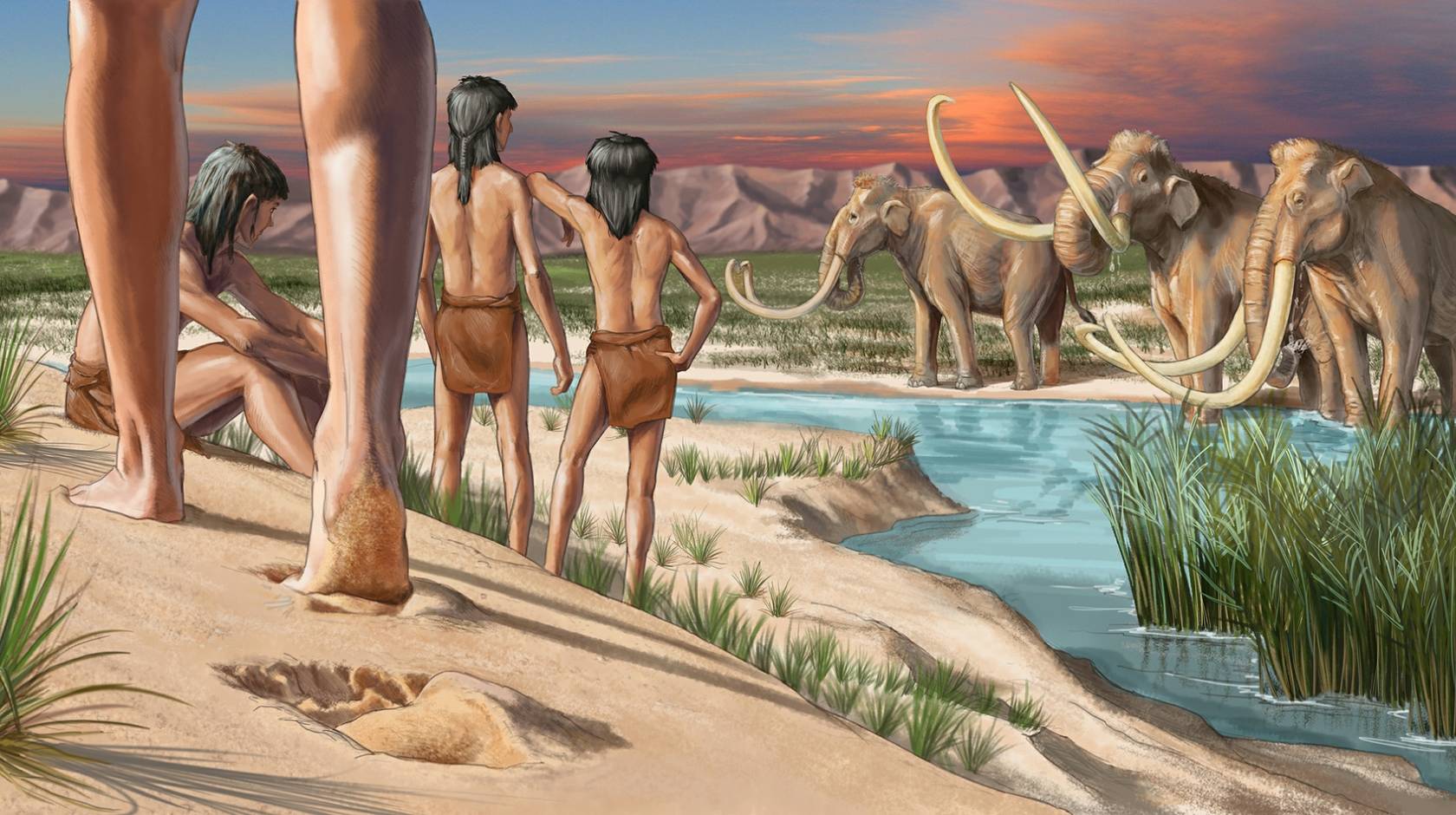

The standard story of the peopling of the Americas has Asians migrating across a land bridge into Alaska some 14,000 years ago, after Ice Age glaciers melted back, and gradually spreading southward across a land never before occupied by humankind.

But the claim in 2021 that human footprints discovered in mud in what is now New Mexico were between 23,000 and 21,000 years old turned that theory on its head.

Now, a new analysis of these footprints, using two different techniques, confirms the date, providing seemingly incontrovertible proof that humans were already living in North America during the height of the last Ice Age.

The study, led by a team of researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and co-authored by David Wahl, a UC Berkeley adjunct associate professor of geography and a USGS scientist specializing in pollen analysis, was published today in the journal Science.

"When the original paper was published in 2021, the authors were very cautious about claiming a paradigm shift, which is what this is all about," Wahl said. "I mean, if people were here 7,000 years prior to the Clovis culture, why don't we see more evidence?"

The Clovis culture, named after a 13,500-year-old site in New Mexico, is characterized by distinct stone and bone tools found in close association with Pleistocene or Ice Age animals, including mammoths, and is considered by many archeologists to be the first human culture in the Americas. Even though there are increasing reports from other sites around North and South America where humans appear to have been killing animals or occupying settlements as early as 16,000 years ago, the Clovis-first theory is still dominant.

So, when USGS researchers and an international team of scientists claimed an age of 23,000 to 21,000 years for seeds found in the footprints — thousands of these footprints are preserved in an alkali flat in White Sands National Park — the pushback from archeologists was extreme.

One point of contention was that the seeds came from a common aquatic plant, spiral ditchgrass (Ruppia cirrhosa). Dating aquatic plants can be problematic, Wahl said, because if the plants grow totally submerged, they take up dissolved carbon rather than carbon from the air. Dissolved carbon can be older because it comes from surrounding bedrock, potentially causing the age measured by radiocarbon dating to be older than the material analyzed actually is. Hence, the reanalysis.

“The immediate reaction in some circles of the archeological community was that the accuracy of our dating was insufficient to make the extraordinary claim that humans were present in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. But our targeted methodology in this current research really paid off,” said Jeff Pigati, USGS research geologist and co-lead author of the new study.

For the newly published follow-up study, the researchers focused on radiocarbon dating of conifer pollen — more than 75,000 pollen grains per sample from fir, spruce and pine, which are terrestrial. Wahl, Marie Champagne and Jeff Honke of USGS worked with Susan Zimmerman at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory to painstakingly isolate the pollen grains through several steps including physical and chemical separation, followed by purifying via flow cytometry at the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at Indiana University (FCCF). The carbon isotope composition of each sample was then determined using mass spectrometry at the Center for Mass Spectometry (CAMS). Importantly, the pollen samples were collected from the exact same layers as the original Ruppia seeds, so a direct comparison could be made. In each case, the pollen age was statistically identical to the corresponding seed age.

“Pollen samples also helped us understand the broader environmental context at the time the footprints were made,” Wahl said. “The pollen in the samples came from plants typically found in cold and wet glacial conditions, in stark contrast with pollen from the modern playa, which reflects the desert vegetation found there today.”

In addition, Harrison Gray on the USGS team used a different type of dating called optically stimulated luminescence, which dates the last time quartz grains were exposed to sunlight. Using this method, the team found that quartz samples collected within the footprint-bearing layers had a minimum age of about 21,500 years, providing further support to the radiocarbon results.

“We were confident in our original ages, as well as the strong geologic, hydrologic and stratigraphic evidence, but we knew that independent chronologic control was critical,” noted Kathleen Springer, USGS research geologist and co-lead author of the paper.

With three separate lines of evidence pointing to the same approximate age, it is highly unlikely that all are incorrect or biased and, taken together, they provide strong support for the 23,000-to-21,000-year age range for the footprints.

"Critics asked us to provide more than one piece of evidence, and we've given them a total of three," Wahl said. "So, we're feeling really good."

Four human footprints found in alkali sand at White Sands National Park in New Mexico. The prints date from 23,000 to 21,000 years ago, long before humans were thought to have first entered North America.

One implication of 23,000-year-old human footprints in North America is that America's first settlers may have originally come through Alaska before the land was covered by glaciers 20,000 years ago rather than afterward, as presumed when human occupancy was thought to have begun 14,000 years ago. Another alternative is that the settlers traveled along the coast.

The research team also included scientists from the National Park Service (NPS) and Bournemouth University in Poole, United Kingdom. At White Sands, the USGS team's continued studies, which focus on the environmental conditions that allowed people to thrive in southern New Mexico during the Last Glacial Maximum, are supported by the USGS’s Climate and Land Use Change Research and Development Program and the USGS-NPS Natural Resources Protection Program.

Related information

The USGS team at work in a trench in a former lakebed at White Sands National Park, New Mexico.