UC Newsroom

The University of California enjoys a long tradition of international service, exemplified by its association with the Peace Corps, dating back to the organization's founding more than 50 years ago.

It continues in the 21st century, with six UC campuses among the Peace Corps' 2014 list of top volunteer-producing colleges and universities:

- UCLA ranked sixth this year with 67 alumni serving. Overall, 1,910 UCLA graduates have served in the Peace Corps since its founding in 1961, the seventh most of any college or university.

- UC Berkeley ranked seventh this year with 66 alumni serving and is the all-time leading university with 3,576 volunteers.

- UC San Diego ranked 12th, with 54 alumni serving. Since the Peace Corps inception, 774 have volunteered.

- UC Santa Barbara ranked 13th with 48 alumni serving. It has the 12th-most volunteers of all-time with 1,611 volunteers.

- UC Davis and UC Santa Cruz tied for 19th place with 41 alumni each. UC Davis ranks 16th for most volunteers of all time with 1,429 people serving, while 787 UC Santa Cruz graduates have been in the Peace Corps.

“The same passion that launched the Peace Corps more than 50 years ago fuels progress in developing countries today thanks to the leadership and creativity that college graduates bring to their Peace Corps service,” said Carrie Hessler-Radelet, acting director of the Peace Corps.

The University of California’s association with the Peace Corps dates back to UCLA serving as one of the first training sites in 1961. UC campuses consistently have been top producers of volunteers, and more than 10,000 UC alumni have served.

Peace Corps volunteers live and work in communities around the world with the goal of promoting a better understanding between Americans and the people they serve.

“The unique Peace Corps experience helps recent graduates cultivate highly sought-after skills that will launch their careers in today’s global economy,” Hessler-Radelet said.

Building and sharing skills

While some volunteers seek to develop skills, others were driven by the desire to travel to exotic places; others by adventure; others still by the passion to be of service. Whatever their initial motivations, all leave their Peace Crops service with a profoundly changed view of the world and themselves.

"As a result of my service in the Peace Corps, I do believe that I've lived its original goals of contributing skills and expertise, learning about another people and culture, and bringing that learning back home," says Jeff Mitchell, an agriculture extension plant specialist at UC Davis who served in Botswana from 1978 to 1982.

"I have a better understanding and sense about the lives of folks in that region of the world and also a greater respect for the challenges they face," Mitchell said. "In my own small way perhaps, I might have contributed to the educational development of this country at a time in its history when it needed such help."

Mitchell taught in a government secondary school that took in boarders from all parts of the country. He had planned on going to law school after his term was up. Instead, he earned master's and doctoral degrees in agricultural science at UC Davis with the idea of working in international development.

"As things have turned out, I've pretty much dedicated myself to research, teaching and extension education work right here in California," he said. "But I have also had opportunities to contribute indirectly to international development goals."

Give a man a fish pond

Kristen Bole, a media relations specialist at UC San Francisco, served in the Central African Republic from 1986 to 1988 as an inland fisheries volunteer, teaching farmers how to raise fish. "Not just giving them a fish," she said. "Or teaching them to fish, but actually teaching them how to build a pond and raise fish."

Like most Peace Corps volunteers, she found herself getting involved in projects outside her actual assignment, like helping women build fuel-efficient woodstoves and working in the local clinic.

"I think Peace Corps volunteers get far more out of their experience than they actually give to the host country," Bole said. "We all go over with the sense that we're going to 'help' and have an impact, but you realize once you're there that the problems you thought you could solve are immense and incredibly complex, and that your greatest contribution is entirely personal and has nothing to do with your initial assignment."

About a week before Bole left Africa, she went to visit a friend who was a prostitute. As she was leaving the visit, the woman asked if Bole would do her a favor.

"After two years of being asked daily for money or candy or my hand in marriage, I groaned inside at one more request, but tried to smile and ask what she wanted. She said, 'Could you teach me to read before you go?' "

Learning to listen

Just about the time Bole was finishing her Peace Corps service, Catherine Thomsen, a public health project leader with the UC-managed California Breast Cancer Research Program, was heading for Costa Rica where she served from 1988 to '92, half of that time in an isolated village near the Nicaraguan border. She learned everything from making tamales to playing the guitar so she could teach songs to the children in the kindergarten she created. But she learned a lot more than cooking and musical skills.

"There were moments of challenge and frustration," she said. "It took time and effort. That was an important lesson I learned, to sit back and listen more."

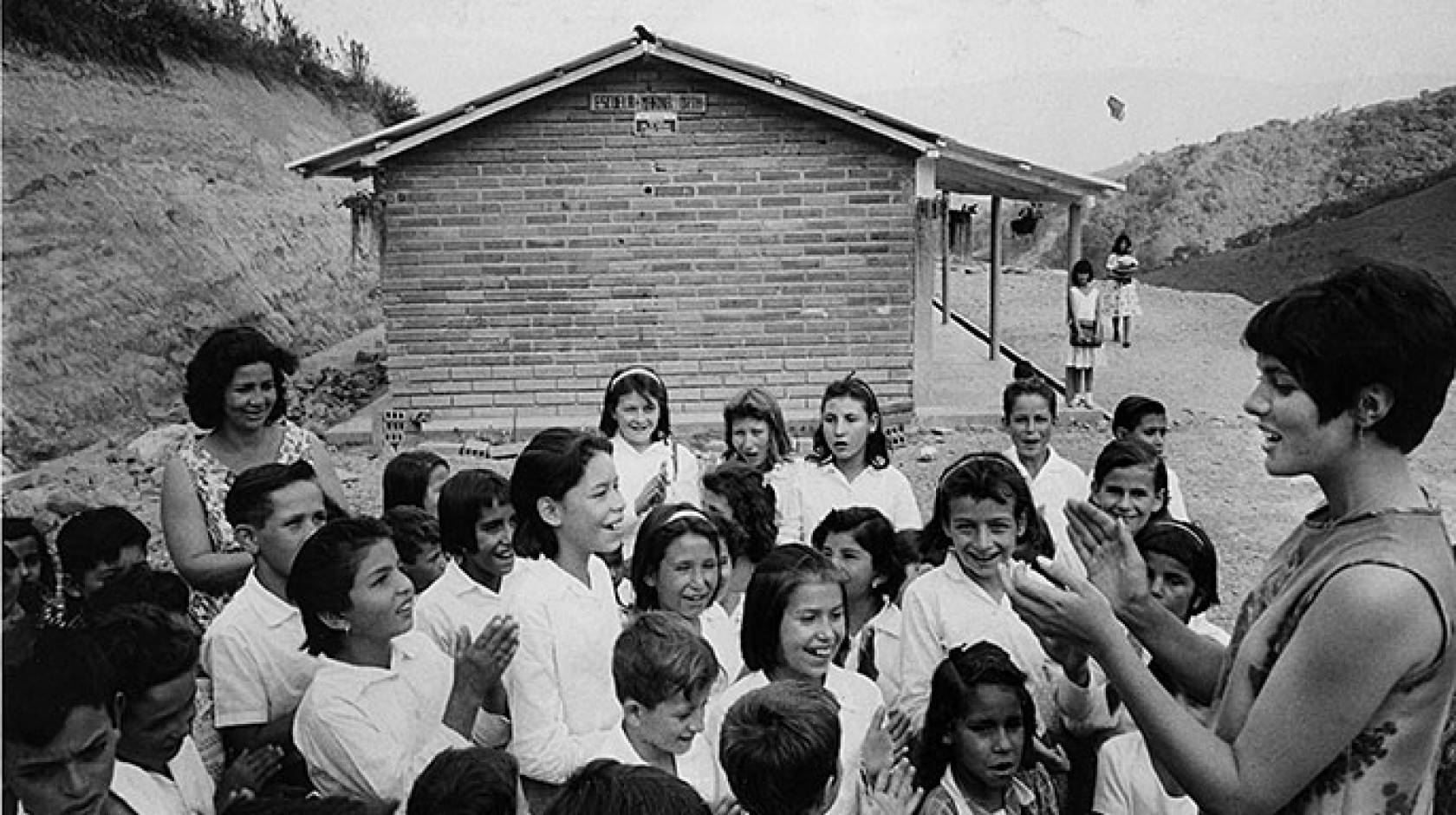

When she asked the people what they wanted to learn, they told her they wanted information about nutrition and how to keep their children from catching colds and flu. She helped organize a government speaker series to bring that educational material to the village. Thomsen then worked as a Peace Corps volunteer with the USAID traveling around Costa Rica working with other volunteers. One of her projects was the opening of a brick schoolhouse in a town where children had been sitting on logs in a lean-to.

Lifelong connections

UC Davis alumnus Robert Griffiths taught English in a community school in Kenya, 20 kilometers north of Lake Victoria. The school received no government support, so the headmaster would kick students out of class until their families could pay the fees.

Griffiths had eight students who were particularly bright but also poor enough to be regularly kicked out of school. Griffiths' mother worked at an office at Stanford where he had had a summer job. He asked the people in the office for small donations of $10 to help pay the fees, which they were able to do for a year until the students completed secondary school.

"About 10 years later, I went back to visit my school and tracked down many of these eight students," Griffiths said. "Seven of them had completed at least a bachelor's degree at the university."

One got a master's degree and published poetry in Swahili. His youngest sister is named Patricia, after Griffiths mother. Another was teaching math and physics at a government high school.

"He proudly introduced me to the rest of the staff in the teachers' room, telling them that I had helped him get an education and succeed in his life," said Griffiths, who teaches English as a second language and job skills to adults at the downtown campus of the City College of San Francisco.

Big challenges and small changes

Ariana Metchik, a 2005 UCLA graduate, spent two years as a community health educator in Mauritania, a West African Islamic country bordered by Senegal, Malawi and Algeria. She worked on AIDS education and polio immunization programs, organized traditional midwife training and started a health club for elementary students. But living in a patriarchal community where women had few rights was bit of a culture shock, she said — one that inspired her to start a literacy program for the women in her village, most of whom had never seen a written word. By the time she left her post in 2007, they hadn't exactly learned to read and write, she said, "but there was a whole group of women who thought there were possibilities for themselves. I think they loved learning, and I think it instilled in them the idea of a world where their daughters could learn."

Metchik met her boyfriend in the Peace Corps. Fellow Mauritania volunteer Keith Gaddis, a UCLA doctoral student in ecology and evolution, lived in the regional capital of Atar and worked with the mayor's office on setting up a trash disposal plan for the town. He later moved to the national capital and worked on after school mentoring programs for high school girls. He doubled the number of mentoring centers to 16 and started 10 more for elementary school students.

"It humbled me," Gaddis said. "At the same time it gave me a lot more confidence. It made me feel like I was resourceful."

Changes that last a lifetime

Bryant Wieneke, a UC Riverside alumnus, served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Niger teaching, in French, at an agricultural school from 1974 to 1976. The fact that he knew nothing about farming and didn't speak French gave him the confidence, he said, to think nothing is impossible.

"Another lasting effect of the Peace Corps for me was that it was the beginning of a rich life of service, which is the most rewarding way to make a living in my opinion," said Wieneke. "My life in public service emanated from my Peace Corps experience, and I wouldn't trade it for anything."