Anne Brice, UC Berkeley

The Silk Road is an evocative name that, to many, conjures up images of camel caravans and bustling bazaars — an international highway of commerce where people and cultures from the East and West intermingled and traded goods.

But scholars say that this romantic image is only a sliver of what life might have been like on the ancient Eurasian trade routes. UC Berkeley is opening the P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Center for Silk Road Studies, the first institutionalized center in the U.S. dedicated to the study of the historical trading networks serially known as the Silk Road, thanks to a $5 million gift by two branches of the Tang family — Oscar Tang and his wife, Dr. Agnes Hsu-Tang, who are based in New York City, and Bay Area UC Berkeley alumni Nadine Tang and Leslie Tang Schilling, with their brother Martin Tang in Hong Kong.

Credit: UC Berkeley photo by Peg Skorpinski

Chinese American philanthropist Oscar Tang founded the first Tang center for excellence in Chinese Humanities, the P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Center for East Asian Art at Princeton University in 2003. In 2015, he and his archaeologist wife founded the Tang Center for Early China at Columbia University. The new Tang Center at UC Berkeley is the latest addition for the advancement of the interdisciplinary study of the historical Silk Road.

Oscar Tang believes that the new Tang Center at Berkeley is “part of my family’s ongoing effort to enhance knowledge and understanding of the great Chinese civilization and its relationship to the rest of the world.”

The center, which launched April 29, will promote the research and teaching of the material and visual cultures that flourished along the Silk Road and formed a bridge between the many economic epicenters of Eurasia and China. A better understanding of the Silk Road’s history will also help contextualize its emergent geopolitical significance in the present time.

Credit: UC Berkeley photo by Peg Skorpinski

UC Berkeley is home to a diverse group of scholars who are leading specialists in the languages, history, religions, intellectual and artistic traditions of the ancient civilizations of China, Central Asia and the Near East, making the campus a natural site for a specialized center dedicated to studying the Silk Road.

The center will fund fieldwork and fellowships for faculty and students at excavations, museums and archives; organize conferences and workshops to bring distinguished scholars to campus to share recent discoveries and research; advance teaching on Silk Road topics; foster visiting scholar exchanges; support open-source publications; and promote the training and outreach of K-12 teachers and community college instructors.

Credit: UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small

Among the UC Berkeley scholars on the center’s advisory committee are Jacob Dalton, a professor of Tibetan Buddhism; Patricia Berger, a professor of Chinese art; and Sanjyot Mehendale, a lecturer of Central Asian art and archaeology, who will serve as the inaugural chair of the new Tang Center. Renowned cellist and humanitarian Yo-Yo Ma and Francesco Bandarin, UNESCO assistant director general for culture and a UC Berkeley alumnus, will serve as the center’s honorary advisers.

Mehendale says the center will foster the multidisciplinary collaboration necessary for Silk Road research. “It’s about coming together and poring over material from different sides,” she says. “You can’t just sit in your corner of expertise. You have to look at the art, you have to study the texts, you have to examine the archaeological remains, to build a bigger picture. The more we understand the history of the region, in particular Central Asia, the more it will resonate as a place, as cultures, as people.”

Understanding the ancient civilizations on the Silk Road requires an expertise in Buddhist studies, of which UC Berkeley is a leader. Established in 1972, Berkeley’s Ph.D. program is the only freestanding doctoral program in Buddhist studies in North America. An important component of this program is the study of Buddhist textual materials in classical languages, many of which have not been spoken for centuries.

Credit: UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small

Robert Sharf, a professor of Buddhist studies at UC Berkeley, says that studying these texts helps scholars rediscover the lost Buddhist civilizations that once flourished along the oasis towns of the Silk Road but have become forgotten since the mid-eighth century.

“The civilizations of the ancient Near East, South Asia and East Asia all came together and interacted along the thriving urban centers of the Silk Road, giving rise to marvelously sophisticated and innovative cultural achievements,” says Sharf. “The more you learn about that world, the more humble you are. It puts the cultural hubris of our modern world — the idea that we stand at the very apex of human self-understanding — into context.”

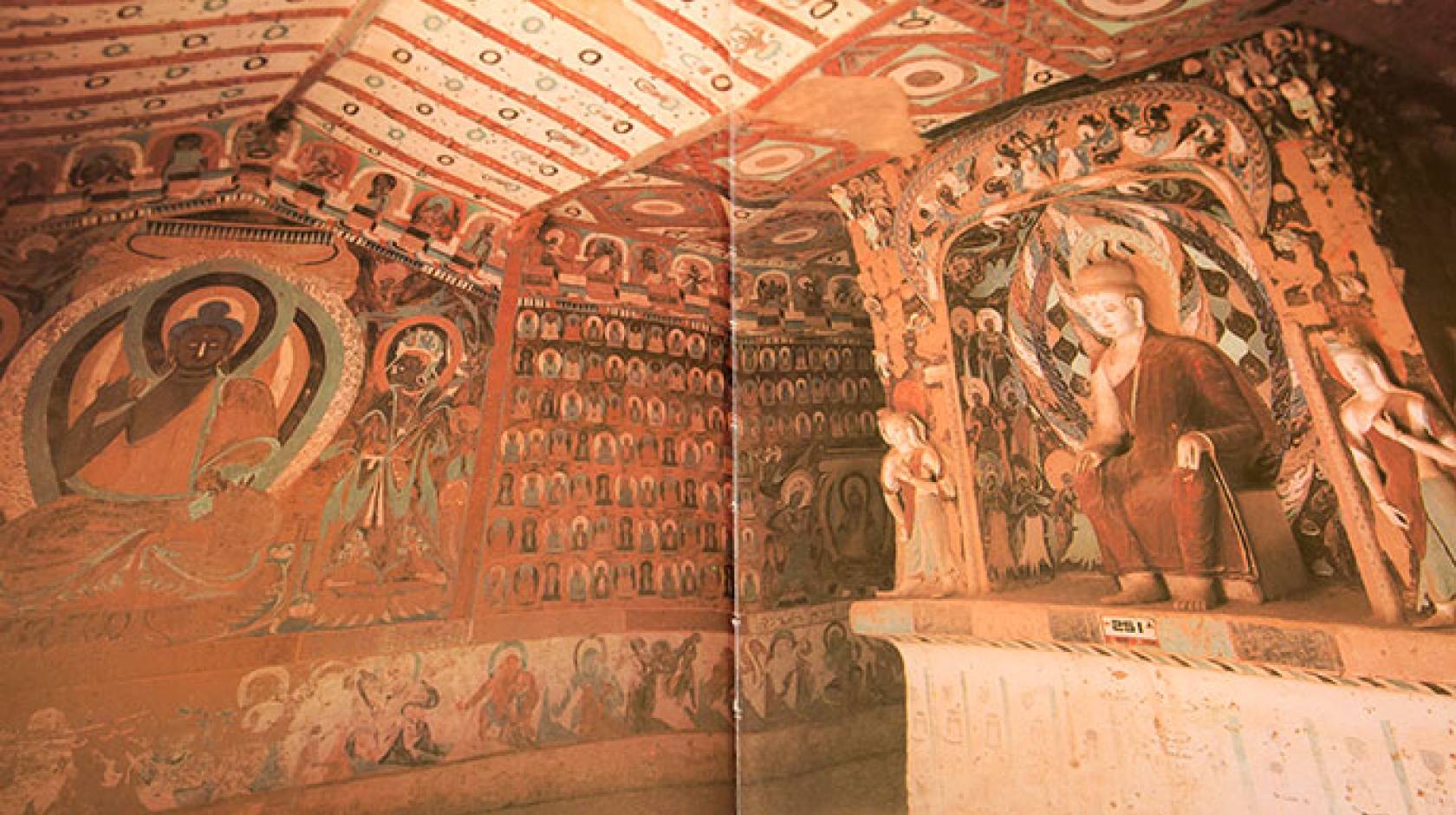

Many of the archaeological, art historical and textual remains left behind on the trade routes are now found at hundreds of remote cave sites scattered throughout far-western China in Xinjiang and Gansu, such as those at Kizil and Bezeklik. The most well-known of these sites, the Mogao grottoes, is located near Dunhuang and contained the world’s largest collection of Buddhist art and manuscripts; its famous “library cave” revealed tens of thousands of invaluable manuscripts written in at least a dozen ancient languages and is considered one of the major archaeological finds of the 20th century.

Credit: UC Berkeley photo by Brittany Hosea-Small

While the best-known, Buddhism is only one of many components in the history of the Silk Road. The center seeks to bring to light the rich cultural legacies of the Turkic, Iranian and Islamic civilizations, among others, that made Central Asia a locus of robust cross-cultural, social and political synergy.

The Tang Center for Silk Road Studies will build on and expand current institutional resources to further enhance Berkeley’s leadership role in the scholarship and teaching of the complex past and cultures of the Silk Road, a critical part of our shared humanity.

UC Berkeley’s Tang Center for Silk Road Studies launched April 29. To learn more about the center, visit its website or email tangsilkroadcenter@berkeley.edu.