UC Newsroom

UC President Michael V. Drake reflects on the Black workers, scholars, artists and activists who have propelled the University of California — and the world — forward, and the work that remains to be done to achieve our ideals of equality, inclusion and justice.

Follow UC’s social accounts (Facebook: University of California, Twitter: @uofcalifornia, Instagram: @uofcalifornia) as UC celebrates Black History Month to hear the voices of Black students, alumni, staff and faculty from across the UC system sharing their visions for the future, which inspire their work today.

Learn more:

Black Californians have played a significant role in UC’s history. Learn more about the figures President Drake referenced below, and check out UC’s 150th timeline to see their work and the work of others in the context of the university's history.

Ralph J. Bunche

Credit: UCLA

Ralph J. Bunche graduated in 1927 from UCLA as the valedictorian of his class. Bunche would go on to win the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation in Palestine in the late 1940s. He was the first African American and first person of color to be so honored.

An adviser to the U.S. during the “Charter Conference” of the United Nations held in 1945, Bunche played a key role in the creation of the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights. In the late 1940s, he became the U.N.’s chief mediator following the assassination of Sweden’s Count Folke Bernadotte; he helped negotiate the 1949 Armistice Agreements. After winning the Nobel for his efforts, he provided mediation in the Congo, Yemen, Kashmir and Cyprus; he was also an active and vocal supporter of the civil rights movement in the U.S.

As a U.N. document, “Ralph Bunche: Visionary for Peace,” notes, he “championed the principle of equal rights for everyone, regardless of race or creed. He believed in ‘the essential goodness of all people, and that no problem in human relations is insoluble.’”

Annie Virginia Stephens Coker

Credit: Stephens Family papers, African American Museum and Library at Oakland

1929 was a momentous year for Annie Virginia Stephens Coker: One of just two women in her class, she became the first Black woman to graduate from Berkeley Law and the first Black female lawyer in California.

Coker’s long legal career spanned private practice, helping tutor Black students for the bar exam and working as an attorney for the State Office of the Legislative Council in Sacramento. Yet her remarkable life and work would have been forgotten if it wasn’t for the efforts of Brenda Harbin-Forte, a fellow Berkeley Law graduate.

About 30 years ago, Harbin-Forte, an Alameda County Superior Court judge at the time, attended a gathering held by the Historical Society of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, honoring California’s first female lawyers.

No Black women were recognized at the event, a slight that inspired Harbin-Forte to conduct research on the first Black woman to practice law in the state, eventually piecing together Coker’s history by getting in touch with Coker’s colleagues and friends.

In 1987, Harbin-Forte published a story in the Historical Reporter, a publication of the Historical Society of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, that chronicled Black women who broke barriers in California law, including Coker. Harbin-Forte, who herself was the first Black female president of the Alameda County Bar Association, was not surprised to find it was the first time Coker and others were mentioned.

“People just don’t seem to care what Black women think about our own struggles,” she said. “So, it was important to me to share this information, so that other Black women would have historical role models in law.”

As a result, Black law students at UC Berkeley feel a connection to Coker today.

“When you think about the barriers she had to overcome to achieve such feats during a time of blatant discrimination, it’s unimaginable,” Berkeley Law student Linda Blair said. “I just think it speaks to the ability to achieve in a community like Berkeley. It makes me really proud. I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for her.”

[Read more about Coker, her legacy and the work of Harbin-Forte to keep her memory alive at “Legacy of Berkeley Law’s first Black female graduate lives on” by Ivan Natividad, from which this description was adapted].

Roy Overstreet

Credit: UC Riverside

Roy Overstreet was the first African American to receive a degree from UC Riverside, which opened its doors as an undergraduate campus in 1954. Overstreet was a member of that first class, earning a degree in physics. He was one of just two Black students at UC Riverside in that early period, along with Zelma Ballard, who graduated in 1959. The two would grab coffee together on campus. He went on to become the country’s first black oceanographer, and worked for nearly 30 years tracking oil spills and nuclear material in oceans.

Overstreet returned to UC Riverside, which now has some of the highest graduation rates for Black students in the country, in 2011, to speak at UC Riverside's Black Graduation Ceremony. Overstreet, then 76, was touched by the two standing ovations he received. He later told the Press-Enterprise, which covered the event, that he was astonished that a black graduation event could fill the gymnasium of UC Riverside’s Student Recreation Center. “It was mind-blowing,” Overstreet said. “I never would have imagined it.”

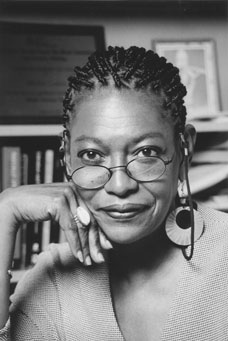

Barbara Christian

Credit: UC Berkeley

Barbara Christian, pioneering scholar of African American literary feminism, was the first Black woman to be granted tenure at UC Berkeley, in 1978. She later became the first Black woman to to be promoted to full professor (1986), and the first to receive the campus's Distinguished Teaching Award (1991).

A founder of UC Berkeley’s African American Studies Department, she is known for works such as “Black Women Novelists: The Development of a Tradition,” and helped bring to prominence writers like Zora Neale Hurston, Toni Morrison and Alice Walker. She also critiqued exclusionary tendencies in literary theory in her famed 1987 essay “The Race for Theory.” Before she passed away in 2000, Christian received the Berkeley Citation, the highest honor bestowed by UC Berkeley.

“She was a path-breaking scholar,” said Percy Hintzen, then-chairman of the department of African American studies upon her passing. “Nobody did more to bring Black women writers into academic and popular recognition.”