Kathleen Maclay, UC Berkeley

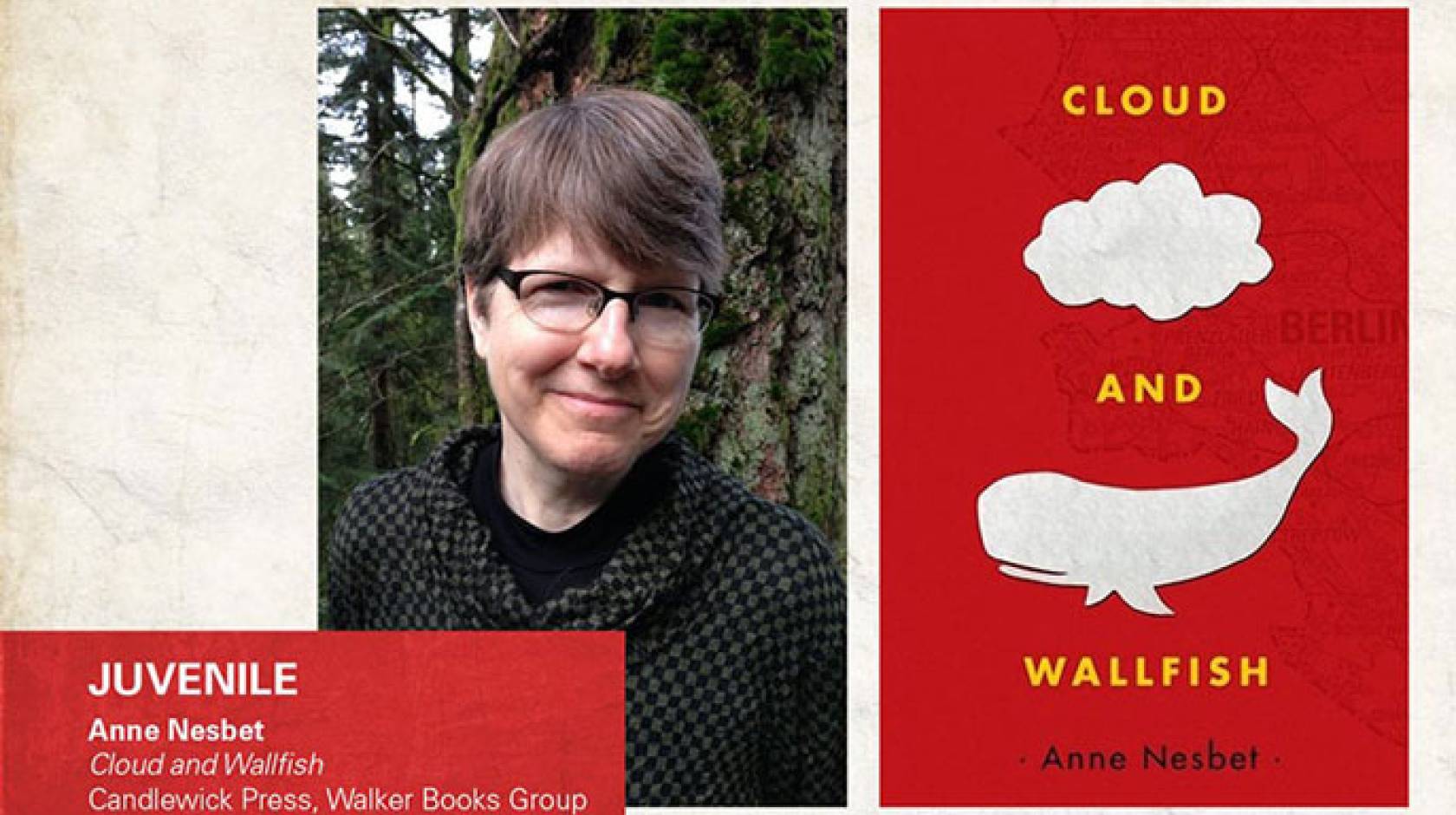

Anne Nesbet joins an illustrious list of UC Berkeley professors to receive a California Book Award gold medal, and is the first to earn the honor for a work of fiction.

Credit: Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Officials with the Commonwealth Club of California will present their annual awards on June 12 to Golden State writers in the areas of fiction, nonfiction, poetry and Californiana. The 2016 gold medal in juvenile fiction will go to Nesbet, an associate professor of Slavic languages and literatures and of film and media studies, for “Cloud and Wallfish,” a historical novel for young readers ages 8 to 14 that is set in East Berlin in 1989.

That’s the year the Berlin Wall fell — and Nesbet stayed in East Berlin to conduct Ph.D. dissertation research about the era after the end of World War II. During her stay, she kept detailed notes and journal entries about the mounting political and social tensions she witnessed and experienced as the underpinnings of the Berlin Wall began to collapse. She returned there in the spring of 1990.

“I was studying one time of dramatic transition at a time of dramatic transition,” she recalled.

Propaganda, fake news and walls

While Nesbet’s fourth work of fiction taps into history that’s nearly 30 years old, she noted in a recent conversation that “Cloud and Wallfish” shines a light on past as well as present concerns — propaganda, fake news, walls and the challenges of ethical living.

The novel tells the story of an American boy transported from a small town in Virginia to a towering apartment building in East Berlin, a city then blanketed by skies turned gray by coal fires. He is told that his mother needs to wrap up scholarly research in the Soviet-occupied part of Berlin, but that seems to be a ruse, as Noah comes to suspect his parents are really undercover spies.

The story follows the developing friendship between the boy and an orphaned girl living with her secretive grandmother as they navigate life in the world’s spy capital and “the city of secret messages.”

Secret files

Credit: Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

Each chapter of the novel ends with a “secret file” that adds historic context and color while explaining information that is likely to be new to young readers and maybe even to teachers who didn’t live through that period.

For example, “Secret File #15/Tunnels and wires” observes that Berlin was rife with secrets.

“The East Germans were spying on the West Germans, and the West Germans were spying on the East Germans. The Soviets were spying on the West Germans and on the Americans and the Americans, French, and British were spying on the Soviets — not to mention, as it turned out, on one another.

“And of course the people who lived on either side of the Wall had their own messages they wanted to convey: I love you. I miss you. How are the parents and cousins doing?”

“Secret File #25/Peeking over” observes the East German newspapers’ fondness for interviewing ordinary, happy workers. “Propaganda was a big part of every newspaper’s job, which meant making East Germany look as good as possible, no matter what. That was getting harder and harder.”

“I wanted them to understand what was going on,” explained Nesbet, adding that the “secret file” device is appropriate for this story also because at the time so many secret dossiers were kept on residents of East Berlin.

“It’s important for people to care about tracing facts back to their roots, and question why things happen,” said Nesbet.

However, she acknowledges in an author’s note at the end of “Cloud and Wallfish”: “Truth and fiction are tangled together in everything human beings do and in every story they tell.”

Legitimizing artistic work

She said she hopes the California Book Award — along with the American Library Association’s selection of “Cloud and Wallfish” as one of its “notable books for children” — helps to “legitimize artistic work on campus,” and expands awareness about the importance of creativity not just in the arts and humanities but across the sciences too.

“It’s helpful for all of us to have creative ways to prime the pump and think about something from different directions,” Nesbet said.

In a previous interview for a UC Berkeley News story about arts and the academy, she noted “a flow, an evolution on campus toward appreciating the creation of art as serious activity. We tend to think of creative endeavors as being distinct from academic work, as mere hobbies. The whole institution of higher education is slow to acknowledge that the creation of art is also an intellectual activity. But, in fact, art and science are profoundly intertwined.”

Other UC Berkeley California Book Award winners

Nesbet was preceded in her award by another UC Berkeley professor of Slavic languages, Czeslaw Milosz, who won a California Book Award gold medal in 2001 for a book of poetry.

Berkeley professors who have won California Book Awards for nonfiction include journalist Michael Pollan, Travis Bogard of theater, dance and performance studies and the late Ronald Takaki. Adam Hochschild, a lecturer in the Graduate School of Journalism, has won in the nonfiction category more than once and was nominated this year for “Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939,” as was sociology professor Arlie Hochschild, for “Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right.”

Literature as work and pleasure

Nesbet, who is editing the manuscript of her second historical novel, is taking time to read for her own pleasure too.

“I read while I walk to school and back,” she says, adding that she does so very carefully and always stops reading when crossing the street.

On her reading list is “Amina’s Voice”, a middle schoolers’ book about a Pakistani American Muslim girl’s challenge to blend in while staying true to her family’s culture, by Hena Khan, and a post-apocalyptic saga, “The Boy on the Bridge”, for adult readers. While she has turned to an e-reader for reading at night or in the rain, Nesbet maintains a preference for words on paper.

“I love having a book in my hands and turning the pages,” she said.