Mike Beck has an enviable commute: an eight-mile drive along the coastal bluffs that separate the city of Santa Cruz from the ocean. In his 25 years as a professor of coastal sciences at UC Santa Cruz, Beck has gotten to know the route well — and he’s watched it change a lot.

“I see where waves are now reaching right up to the roadway, or where our barriers get overtopped,” Beck says. “Just driving along that road almost every day for years, I’ve seen our beaches getting thinner and thinner.”

It’s not just happening in Santa Cruz. Hemmed in by highways and homes to one side and rising, ever-stormier seas to the other, beaches are shrinking up and down the state. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that California could lose three-quarters of its beaches by 2100.

That’s not just a huge bummer for future summer vacations. Dozens of species depend on those sandy shores. Our beaches also provide a natural buffer from flooding, erosion and other natural disasters for millions of California residents.

Beck, who today heads the Center for Coastal Climate Resilience at UC Santa Cruz, has spent his career helping communities understand how and why their shorelines are changing, and what to do about it. He’s in good company at UC, where researchers across the system are focused on understanding and protecting our coast. UC expertise, spanning climate, ecology, oceanography, geomorphology, economics, engineering and social science, informs the day-to-day decisions Californians make about our coasts.

As the climate warms and the oceans rise, the urgency of UC coastal research is rising too. “The decisions our state has to make, about what parts of our coast to defend and how, versus where we retreat from, are going to be difficult,” Beck says. “What I and a lot of my colleagues at UC Santa Cruz and many other campuses are doing, is figuring out how we spend our limited funding on projects that work with nature to get the greatest benefit for the longest time.”

Michael W. Beck, director of the UC Santa Cruz Center for Coastal Climate Resilience.

Beaches were made to move

To understand why our beaches are shrinking, it helps to understand how they got here in the first place. Sandy shores often form in shallow bays and inlets, where they are protected from waves, explains Ian Walker, a geomorphologist and professor of geography at UC Santa Barbara. And they often appear at river mouths, where everything that’s washed down along the river’s inland course settles out in deeper, calmer waters.

California’s coast has always been a dynamic place. Beaches have accreted, eroded and migrated with changes in sea level, tides and climate. These changes play out across geologic time, which isn’t to say they can’t happen fast: As the last ice age ended between 20,000 and 12,000 years ago, seas rose by an average of a meter per century.

“When sea level was 300 feet lower than it is today, there were beaches down there,” Walker says. As continental ice sheets melted and the seas rose, beaches recreated themselves at the new higher tide line. It happened fast enough that people living along the coast of California 12,000 years ago would have noticed the change within a single lifetime, or at least from generation to generation.

For the past 6,000 years, sea levels have been relatively stable. “Many of our beaches have been sitting here kind of bored, collecting sediment, but not moving much compared to how they did following the collapse of the last ice age,” Walker says. “So our relationship with the coast in California is one of a fairly limited understanding of change.”

Believing our beaches more stable than they actually are, we’ve built neighborhoods, highways, railroads and power plants within sight of the ocean. Now the climate is warming again. “Left to their own devices, beaches will want to move landward and upward again as they did 20,000 years ago,” Walker says. But their retreat is blocked: Walker calls this phenomenon “the coastal squeeze.”

The problem isn’t just with coastal infrastructure. “We’ve dammed up most of our rivers, and dams retain a lot of sediment,” says Brett Sanders. He’s a professor of civil and environmental engineering and leads the Flood Lab at UC Irvine. Research from UC Santa Cruz found that two-thirds of the sand that used to make it to the coast is trapped on land. “Most of the beach erosion now we're seeing in Southern California is from decades of sand starvation,” Sanders says.

Today the beaches Californians know and love are at least as much a product of human engineering as natural processes, notes Sanders. Prior to widespread development of the California coast, beaches were typically narrower, and they waxed and waned seasonally. But in the 20th century, we built lots of harbors and ports, which involved digging out coastal wetlands and depositing the sand onshore. By the 1960s, Southern California’s beaches were wide and spacious all year.

Those big, inviting beaches became a part of California’s identity, economy and infrastructure, Sanders says. People wanted to visit and live near the coast, so we built more cities and roads to accommodate. But as the midcentury coastal building boom tapered off, so did the big infusions of sand that had bulked up the state’s now-famous beaches. Meanwhile, the ocean continued its steady work of washing away the sand that’s there.

“It was like we put a bunch of money in the bank, and now our balance is running low,” Sanders says.

Today many of the state’s widest and most visited beaches owe their continued existence to human intervention. Sometimes the beach is incidental: Scripps Institution of Oceanography scientist Reinhard Flick noted that every time harbors around San Diego get dredged, crews deposit some of that sand on nearby beaches like Coronado. In other cases, the beach is the point. The City of San Clemente recently embarked on a $16 million effort to scoop up 251,000 cubic yards of sand from the seafloor and put it onshore, aiming to make a half-mile stretch of beach 50 feet wider.

Beck points out another crucial human intervention: the creation, almost 50 years ago, of the California Coastal Commission, the state agency tasked with protecting the coasts in perpetuity. “Say what you will about our past decisions, but today California enjoys some of the world’s strongest coastal decision-making,” Beck says. His recent research has taken him to Belize, where “a lack of comprehensive management and a lack of understanding of shoreline evolution means it’s every person for themselves. You can take the sand from your neighbor to shore up your own beach. In California, that’s not the case, and that’s a luxury we enjoy.”

Meanwhile, California’s sand-starved coasts are meeting an ocean that’s both higher and more powerful, a result of our warming climate. “Adding warmth to the atmosphere really means you’re adding more energy,” says Beck. That’s causing stronger storms, which can wipe out whole beaches — and millions of dollars of beachfront real estate — in one fell swoop. And a more energetic atmosphere produces stronger winds and bigger waves throughout the year.

What we lose when we lose beaches

"Beaches are so important to the culture and the region,” Sanders says. They’re one of the most accessible and affordable ways for Californians to get outside: a survey from the California Coastal Conservancy found that 20 million California adults, or two-thirds of the state’s adult population, visit the beach at least once a year. And the survey suggests that even folks who can’t visit the coast in person might be daydreaming about it: nearly 90 percent of Californians said the coast was personally important to them, and 94 percent said that people of all backgrounds are welcome at the beach.

Beaches also have considerable economic clout. They’re the heart of a tourism industry that brought in $135 billion in 2022 alone. And Beck says they’re “our second line of natural defense against coastal flooding,” behind offshore reefs and rocks. “The height of your beach and dune system, that’s how much flood protection you get, and that’s really a significant level of protection,” Beck says.

Walker notes that California’s beaches defend dunes, lagoons and wetlands that can store appreciable amounts of carbon in soil and vegetation. As these environments erode and disappear, that carbon eventually gets released into the atmosphere, where it can contribute to global warming.

What the future might hold

The best estimates from the State of California project sea level rise between half a meter and a meter by 2100. Absent intervention, that's likely to wash away at least quarter of the state’s sandy beaches. Researchers across UC are delving into that projection and piecing together how the forces that are shrinking California’s beaches affect each stretch of the coast differently.

Walker notes that socioeconomics help determine the resilience of coastal communities and the shorelines they live along. “A low-income community near the coast is often much more vulnerable than a more affluent neighborhood, even with comparable physical exposures,” Walker says. The richer community “can afford to hire consultants, can lobby for support in ways that a disadvantaged community might not be able to.”

Research backs this up. A study from North Carolina found that more affluent communities are more likely to build sea walls or restore their beaches by adding sand. Lower-income communities are more likely to be offered buyouts, which means giving up their homes in the face of rising seas and moving elsewhere. And the costs of living along the coast in Southern California could quintuple by 2050, driven by the escalating need to fund dune and beach restoration as sea level rise accelerates.

How UC is helping California save its beaches

Attempts to hold the shoreline are nothing new in California. Ice plant, which carpets hundreds of miles of roadsides throughout the state, was introduced in the early 1900s to keep the sand in place under coastal railroad tracks. It excels at that — because it grows in thick, monoculture mats that crowd out native plants and alter soil chemistry. These characteristics have earned ice plant a spot on the State Fish and Wildlife’s list of Invasives to Avoid.

The science has gotten better since the age of ice plant, but much remains unknown, Walker says. “For that $10 million restoration you’re putting in the ground, is it actually going to function like a dune and be resilient, or is the beach too narrow? Is the sand supply too limited? Is there enough wind to maintain it? Right now, some of what’s happening is not fully informed by the state of the science,” he says.

The State of California is making big investments in coastal climate resilience, with help and expertise from UC researchers and scientists. “Given the magnitude of interest and investment in sea level rise, more can be done to pull it all together and come up with best practices,” Walker says. He’s leading a two-year effort to compile findings from 20 dune restorations throughout California and create a new framework to guide decision-making for future projects.

In places where restoring self-sustaining dunes isn’t an option, periodically digging sand up off the seafloor and depositing it on the shore is the next best thing. Beach nourishment, as the practice is known, is an expensive endeavor that carries environmental risks, Sanders says. “That being said, Southern California naturally had many, many sandy beaches, and these armored, completely exposed coastlines we face today are not healthy ecosystems.” Putting sand back onshore might not be a natural process, but Sanders argues that “there are many parts of the coast where adding sand will actually help restore a natural ecosystem as long as it is done carefully to minimize ecosystem impacts.”

Engineers hope to get years to decades out of each beach nourishment project, but that doesn’t always work out: last year, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spent tens of millions of dollars to bulk up beaches along the Jersey Shore, only for most of that sand to wash away over the winter. How can California communities make sure the same thing doesn’t happen to them?

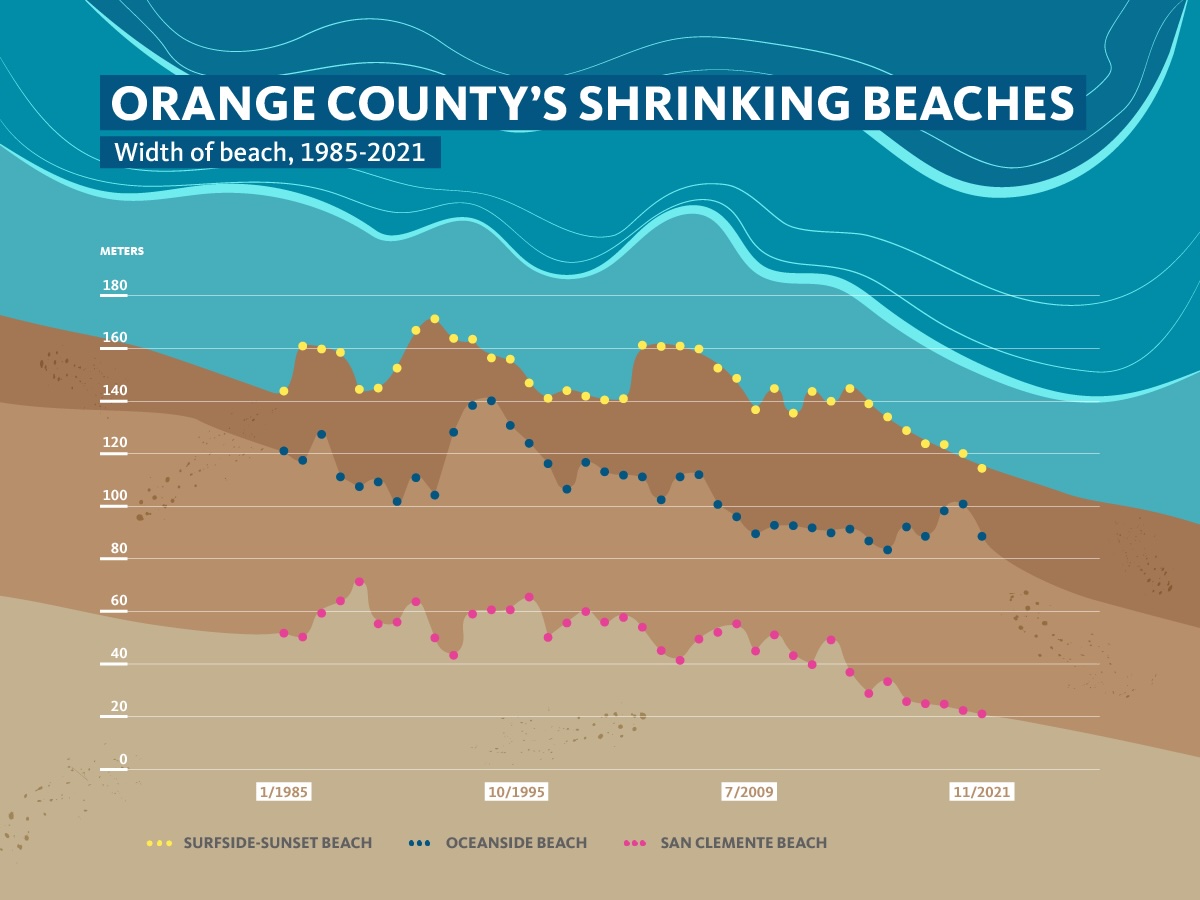

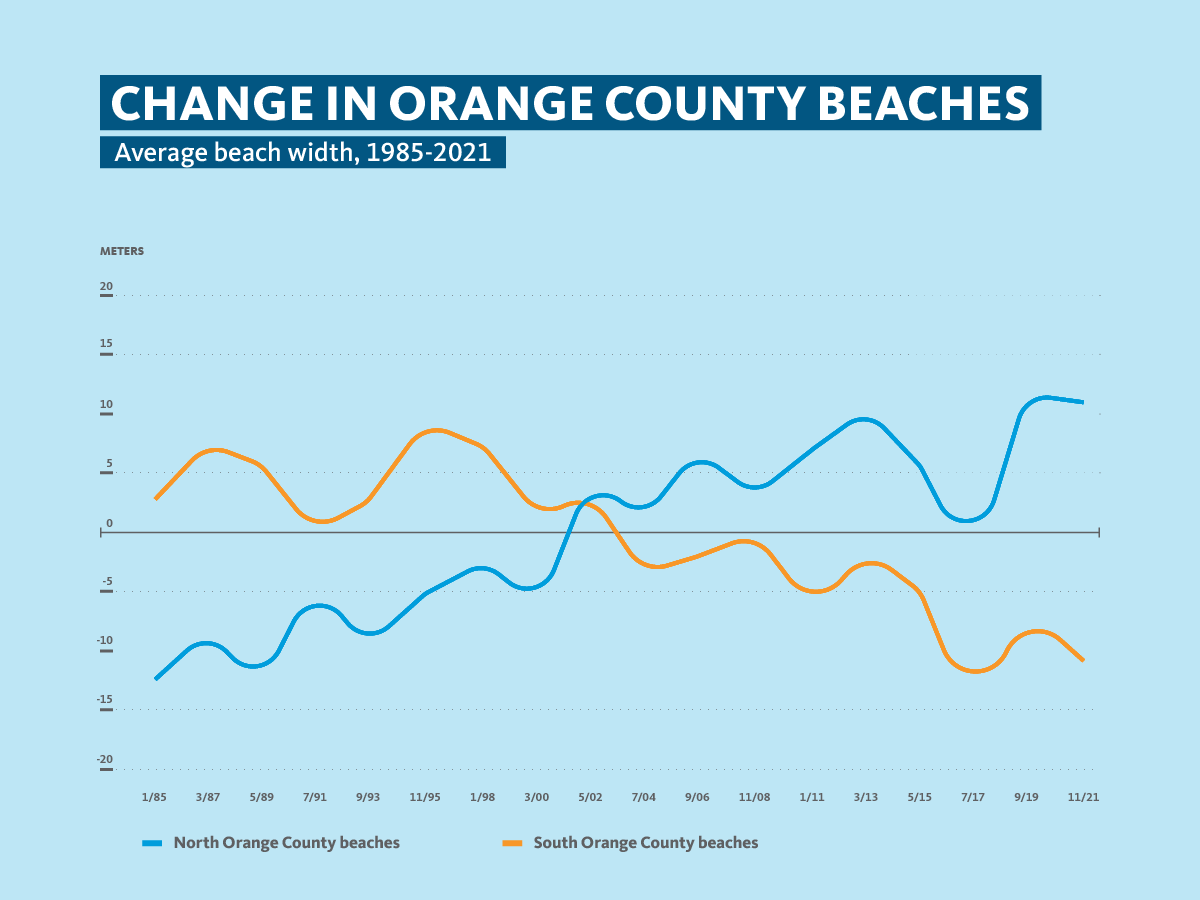

While working toward a Ph.D. in Sanders’s Flood Lab at UC Irvine, Daniel Kahl has scrutinized decades of aerial imagery along the coast between Los Angeles and La Jolla. He recruited a small army of undergraduate researchers to measure the beach at 100-meter intervals in historical aerial images, building a data set that describes in usefully intricate detail how the O.C.’s beaches have changed over the past century.

This data has also informed Kahl’s inquiry into how sand moves along the coast — and his findings are turning over some longstanding assumptions and could change the future of beach nourishment throughout the state. Since the 1950s, Kahl explains, conventional wisdom has held that the northwesterly waves approaching the coast of southern California generally push sand from north to south, just like the rest of California. “However, what I’ve found is that southern swells — which are more prominent along southern California coast — push sediment from south to north, and on average, the net transport is south to north at many beaches.”

Kahl developed a diagram showing how sand moves along the region’s coast and he’s been sharing this with communities across southern California confronting beach loss. “We have a lot of sand going in the opposite direction than what’s expected,” Kahl says. “It’s actually kind of blowing people’s minds.”

Now, Kahl and Sanders are using these findings to help O.C. communities spend beach nourishment money wisely. “Beach nourishment is costly, and we can maximize the cost-effectiveness of projects by working with — and not against — the prevailing transport directions,” Sanders says. “Dan’s data is especially valuable for finding the most promising sites for shoreline stabilization, and documenting where realignment of housing and infrastructure with the changing coastline might be the only feasible option.”

In the coming decades, the fate of California’s beaches — and so much else about life in the Golden State — hinges on the amount of carbon in the atmosphere. But even if we stopped burning fossil fuels tomorrow, “the rates of sea level rise that we will see in the next hundred years could be faster than anything we've seen in the past five to ten thousand,” Walker says.

“We won’t be able to save every beach,” says Sanders. “But we can get a better understanding of which beaches have the most potential to be sustained in the future.”