Nina Bai, UCSF

When it comes to the fat in your diet, the line between good and bad just got blurrier.

Liberal consumption of so-called good fats — like those found in olive oil and avocados — may lead to fatty liver disease, a risk factor for metabolic disorders like Type 2 diabetes and hypertension, according to a new study by scientists at UC San Francisco.

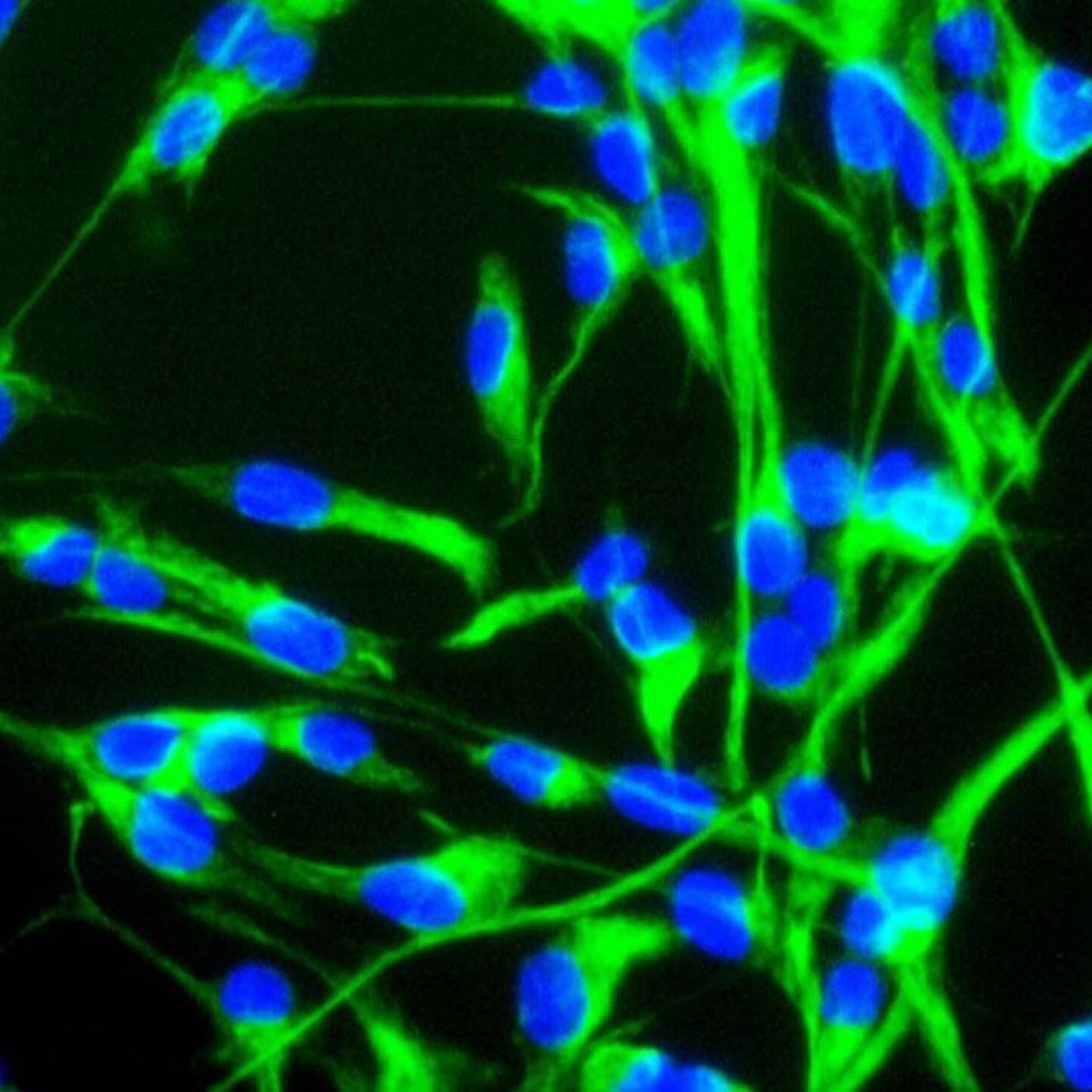

Credit: UCSF

The findings, in mice, surprised even the researchers, who were expecting saturated fat — popularly known as the worse kind — to cause more fat buildup in livers.

“The belief in the field for quite some time has been that saturated fat is bad for the liver,” said Caroline C. Duwaerts, associate research biologist at the UCSF Liver Center and first author of the study, published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Instead, they found that a diet high in monounsaturated fat, combined with high starch content, caused the most severe fatty liver disease. The finding emphasizes that simply counting calories does not guarantee a healthy diet.

“A calorie is not simply a calorie,” said Duwaerts. “What that calorie is made up of is extremely important.”

Moreover, the study shows that monounsaturated fat may disrupt normal metabolism through mechanisms not yet well understood.

A bad combination

The researchers set out to study the role of different nutrients in the development of fatty liver disease, an ongoing project in the lab of Dr. Jacquelyn Maher, director of the Liver Center.

They paired a fat, saturated or monounsaturated, with a carbohydrate, sucrose or starch, to create four different high-calorie diets. The diets were roughly 40 percent carbohydrate, 40 percent fat, and 20 percent protein by calorie, a ratio on par with the average American diet. Four groups of 10 mice were fed the experimental diets for six months and compared to mice fed regular mouse chow, which is much lower in fat.

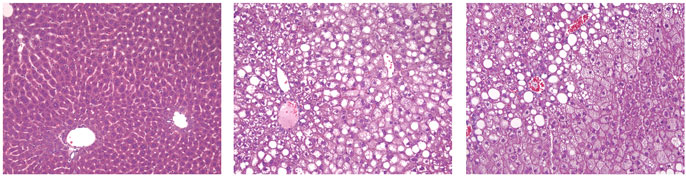

All the mice on the experimental diets, free to eat as much as they wanted, grew obese by the end of six months, and all developed some degree of fatty liver. To the researchers’ surprise, the mice on the starch-monounsaturated fat diet had the most severe disease, accumulating 40 percent more liver fat than mice on the other three diets. Their livers swelled with extra weight and, when seen under a microscope, appeared crowded with globules of fat.

For now, it’s unclear why the pairing of starch and monounsaturated fat seems to exacerbate fatty liver.

Hints and cautions

At the same time, the researchers noticed that these mice lost fat around their testes, an area of their bodies normally used for fat storage. When they examined this visceral fat tissue, they saw an unusual degree of fat cell death and signs of inflammation. Perhaps the starch-monounsaturated fat diet somehow induces the fat from these areas to be shuttled into the liver at an abnormally high rate, fattening the liver. Duwaerts plans to further study how this transfer of fat is affected by diet.

In a final experiment, the researchers fed a group of mice a diet designed to closely mimic the typical Western diet, with a mix of different fats and carbohydrates.

Credit: Image courtesy of Caroline C. Duwaerts

“No human actually consumes only monounsaturated fat as fat,” said Duwaerts, explaining their rationale. Yet even though the Western diet had only a quarter as much monounsaturated fat, the mice developed as much fatty liver as those on the pure starch-monounsaturated fat diet. This suggests that our typical consumption of monounsaturated fat may already be exceeding the healthy threshold.

Duwaerts says it’s all a matter of proportion. A drizzle of olive oil on your salad is fine, but a daily habit of pasta drenched in olive oil could be cause for concern. “I always think back to what I was told as a child,” she said. “‘Everything in moderation.’”