Youssef Benzarti, UCLA via The Conversation

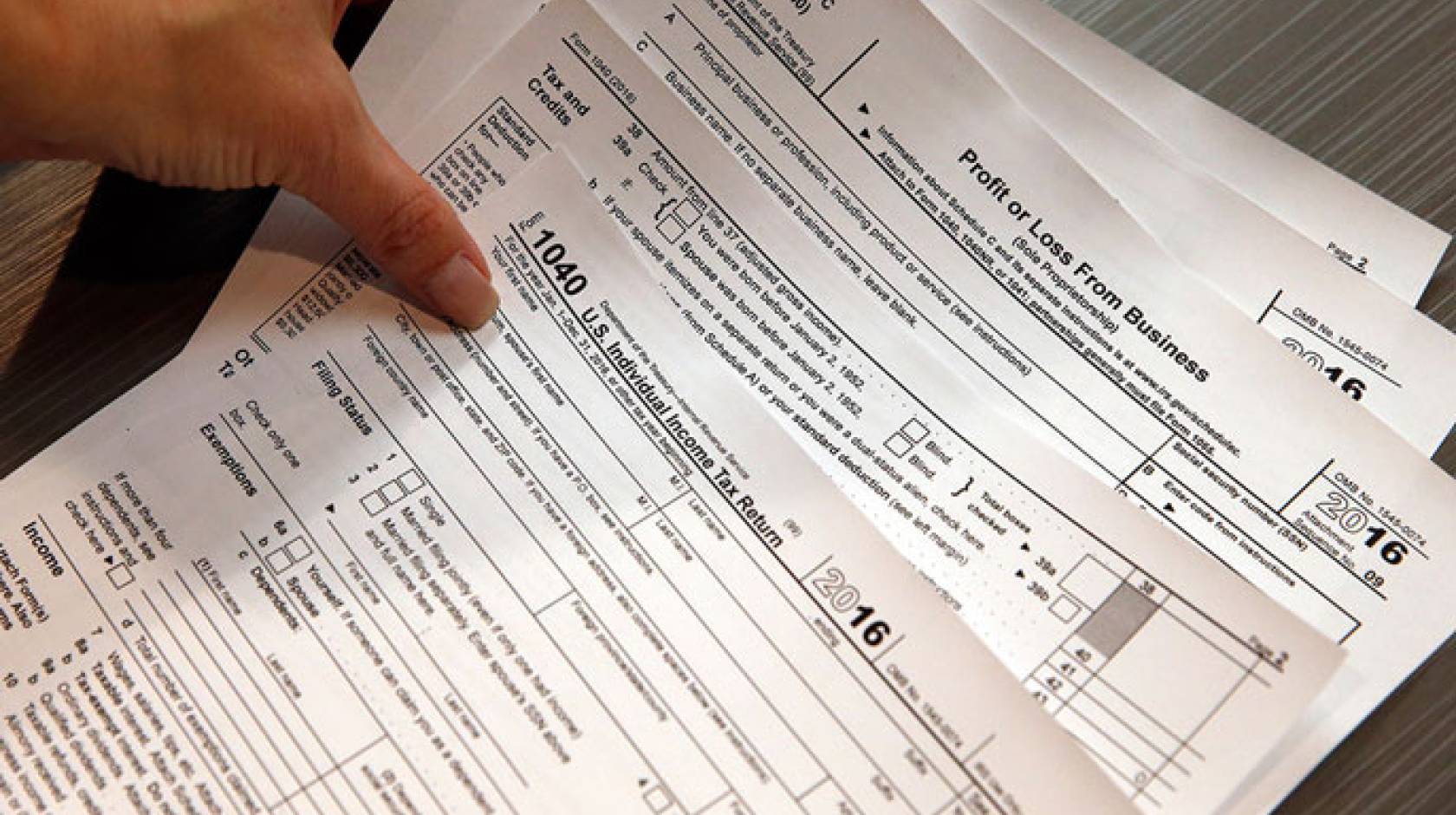

Springtime brings many things, from proverbial showers to birds chirping and warmer weather. It also signals tax season is upon us once more.

Every year 140 million U.S. taxpayers spend countless hours gathering receipts and statements, filling out a variety of schedules and forms, and submitting their 1040s and various other supporting documents to the Internal Revenue Service. This year the deadline is April 18.

As an economist, I wondered whether this tax filing burden results in us paying more taxes than we should. What I found is quite surprising and should be especially disturbing for those of you who still haven’t filed.

A choice of deductions

Income taxes represent the government’s largest source of tax revenue and involve about US$1.54 trillion, or 8.3 percent of GDP, being transferred from our wallets to the federal Treasury every year.

Research into the transaction costs of saving shows that people frequently leave money on the table, such as in saving for retirement and claiming government benefits. I wanted to know if the same thing was happening when we file our taxes.

Individual tax filers can choose whether to itemize deductions, such as for charitable giving or mortgage interest, or claim a standard deduction. Itemizing requires some effort but can provide large tax savings. Opting for the standard deduction saves time but may result in a larger tax tab.

I exploited this choice to estimate the costs of filing taxes. That is, if compliance costs don’t exist, taxpayers would presumably itemize if the benefit of doing so is greater than zero. If there are costs, then itemizing is beneficial only if it reduces the tax bill by more than the cost of itemizing.

Credit: Cheryl Senter/AP Photo

What’s left on the table

When people pick the standard deduction, we don’t actually know how much they could have saved had they itemized.

To get around this problem, I examined data from two years in which there were large increases in the standard deduction: 1971 and 1988. To understand why, imagine that the standard deduction last year was $10,000 and increased this year to $15,000. Now taxpayers with total deductions just above $15,000 will have to decide whether to bear the pain of itemizing or just go with the standard deduction.

By comparing the percentage of taxpayers just above the standard deduction before and after the large increase in the standard deduction, I was able to reconstruct the distribution of foregone benefits. Long story short, it showed me that some taxpayers choose the standard deduction even though itemizing would have saved them money, resulting in an average of $644 being left on the table.

After breaking the results down by income levels, I found that wealthier individuals are more likely to sacrifice the tax savings from itemization to avoid the time it would take to do it. Further calculations led me to estimate that itemizing deductions is perceived on average to take 19 hours of pain and effort.

Altogether, I use this analysis to estimate the burden of filing our taxes. It turns out it amounts to about $200 billion, or about 1.2 percent of GDP, which is two to three times larger than previously estimated.

This is where it gets worse for procrastinators, who pay a price for delaying the inevitable. By waiting until the deadline to do their taxes, I found that people are more likely to forgo those itemized deductions. Perhaps it’s because they lack the time. Or it may be because the perceived time cost of rummaging for all the receipts and papers and doing all the calculations just doesn’t seems worth the effort – even if might be.

Credit: Marcio Jose Sanchez/AP Photo

Why don’t we fix this?

While several countries have solved this problem, the U.S. is trailing behind. The solution to drastically reducing compliance costs is pretty simple and benign, and it’s what countries from Denmark to Chile have done.

It turns out that the Internal Revenue Service knows most of the information that we are required to enter in our return – such as wages, mortgage interest, state taxes, etc. – and could send us prepopulated returns that we could verify for accuracy and sign. The whole ordeal could take less than an hour.

Why are we not there yet? Some suggest that the tax preparation industry may have something to do with it, since anything that makes it substantially easier could cost it potentially hundreds of million of dollars in revenue.

While the IRS’ free file program has made it a bit simpler, it still requires a lot of record keeping, and the percentage of taxpayers who actually file for free remains very low, at few than 3 percent as of 2014.

If Congress is about to undertake a reform of the tax code, reducing compliance costs should be at the top of their to-do list – something to keep in mind as you agonize over this year’s taxes.

Youssef Benzarti is an assistant professor of economics at UCLA. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.