José Vadi, UC Davis

This season, baseball fans can find three UC Davis alumni — Sig Mejdal, Daniel Descalso and Ross Fenstermaker — in key leadership positions within Major League Baseball.

The story of their finding a path into the big leagues starts in 2003 when Mejdal ’89 read an excerpt of the book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game and had a professional epiphany.

The book, written by Michael Lewis, details how then-Oakland Athletics manager Billy Beane utilized underrecognized player stats and data to influence which players he wanted on the roster as affordably as possible.

“I was just, like, ‘My gosh, why didn’t I know of this? This is perfect for me. I need to hurry up and apply before others do.’”

Few major league front office staffers agreed.

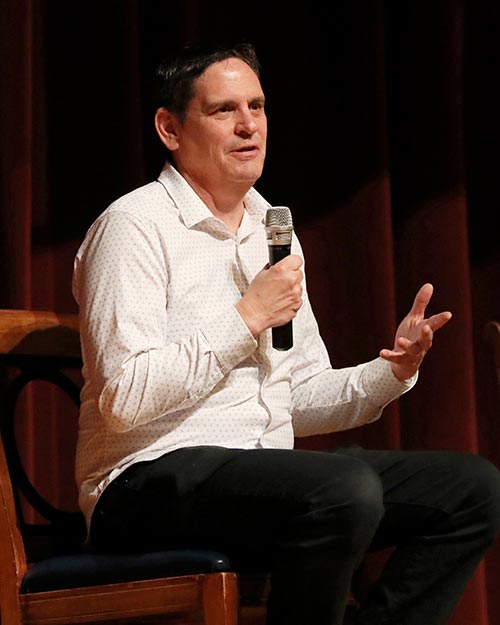

“I was applying to people who, to some degree, their job security depended on not hiring persons like myself,” Mejdal said.

He persevered and in 2005 was recruited by the St. Lous Cardinals as an analyst for the amateur draft, bringing players into the farm league and helping them develop into the majors. He utilized sabermetrics to take available collegiate and summer league stats of potential players and create algorithms projecting their performance. This data-driven approach, while also considering the difficulty of those player’s college programs, schedules and more, allowed Mejdal to make better informed decisions, or better bets.

Mejdal is now the assistant general manager of the Baltimore Orioles after stints with the Houston Astros and the St. Louis Cardinals, with both of those teams earning World Series championships during his tenure. Mejdal received a degree in engineering from UC Davis in 1989 and pursued a private sector career at Lockheed Martin and NASA — until Moneyball changed his course.

Mejdal has experienced “the paradigm shift” of including analytics in baseball decision-making. When Mejdal describes himself as only the fourth analyst in baseball, the exclusivity was a double-edged sword. “That meant that 26 teams felt that the perfect number of analysts was zero.” Today, he noted, the number of analysts in baseball is closer to 700.

“Analytics is not only in demand in baseball, it’s the most in-demand field on this planet,” Mejdal said. “It’s clear that there are many sports teams who are really anchored to evidence-based decision-making.”

As a UC Davis undergraduate, Mejdal spent summer jobs at the casinos of Lake Tahoe, dealing blackjack. He described the experience as a real-life example of textbook lessons such as “human factors engineering.”

“To see firsthand, night after night, how our species struggles with decision-making in a highly variable, probabilistic environment where they have financial stakes in the matter,” he explained, “that’s my job now.”

“Intellectually, we may understand the problem, but that’s not always enough to overpower our intuition.” Data analysis assists with “trying to find a solution and [the] challenge of convincing humans to anchor themselves to a decision.”

Now he says finding a career in baseball is about a love for the game.

“We want persons where this is their dream job and it’s their passion,” Mejdal explained. “In my experience, those are the ones that are just the best: They’re the most innovative; they’re the most reliable; they’re the most careful.”

From player to coach

One of Mejdal’s draft picks for the Cardinals turned out to be a fellow Aggie, Daniel Descalso ’22. The Bay Area-raised infielder was part of UC Davis’ inaugural Division I baseball team in 2004. Though Mejdal and his team took notice in the draft, according to Descalso, many did not.

“I was not very highly recruited out of high school,” Descalso said. “UC Davis was the first place that offered me a scholarship.”

Descalso was part of the championship St. Louis Cardinals team of the 2010-11 season. It was the beginning of a nine-year major league career with stints at the Cardinals, Colorado Rockies, Arizona Diamondbacks and Chicago Cubs before he retired in 2019.

“I always thought that I would find myself doing something in baseball. I just didn’t know what exactly that would look like.”

UC Davis helped Descalso begin the transition from home plate to the dugout by welcoming Descalso back to the classroom in 2022 to complete the handful of classes left toward his economics degree. With his family, including newborn children, a one-hour drive away in Danville, Descalso began commuting between the Bay Area and Davis. No longer a student-athlete, Descalso was now “putting the kids to bed and then go study or finish up a couple assignments.”

“I had classes with some of the baseball players,” Descalso said. “Some people wondered if I was going to the right spot, asking if I was supposed to go to the grad school building. ‘No, I’m just here finishing.’”

He also returned to the Davis baseball program, this time as an undergraduate volunteer assistant, his first foray into coaching. After graduating, Descalso briefly worked with the Arizona Diamondbacks before returning to the dugout in his current position as a bench coach for the St. Louis Cardinals. His responsibilities include managing the run game, using hand signs to communicate with his catcher about infield play decisions. He also builds the spring training schedule, organizing the team and smaller group exercises.

But his new degree has led to unique inroads with other departments. After learning how to code “multivariable algorithms” in an analysis of economic data course at UC Davis, Descalso was able to reach across the aisle from the dugout to the front-office analysts.

“Some of the analysts were working on something, and I recognized the program. They kind of looked at me, like, ‘How do you know about that?’” Descalso said, noting most teams now have analysts writing code to understand player performance. “Just understanding what goes into those models helped me to be able to have conversations with those people that don’t necessarily have a playing background but are a vital part of our organization.”

This awareness, according to Mejdal, speaks of the ongoing “race to search for innovation” within the field of data analytics.

“It’s the skill of combining information from disparate sources,” Mejdal said. “That’s been a dramatic shift in in baseball.”

A focus on baseball

Ross Fenstermaker ’08 knows this shift well. He started his career in baseball in the early 2010s amidst a noisier communications landscape driven by social media and online video. A native of Granite Bay, California, Ross was a left-handed pitcher at Granite Bay High School and UC Davis, where he majored in economics.

“Being a student-athlete and the challenges that come with trying to balance or being an athlete and a student, you know, it’s a lot on the plate,” he said. “I think it shows you what you can and can’t take care of and how you can be resilient and find ways to get the job done.”

Fenstermaker played with Descalso on that inaugural Division I Davis baseball team. He roomed with Descalso their freshman years, and every year in college thereafter. They remain close friends, with Descalso serving as the best man at Fenstermaker’s wedding.

Fenstermaker is now in his 14th season with the Texas Rangers. He was promoted to vice president and assistant general manager for Player Development and International Operations in 2021. He oversees the player development/minor league operations departments along with the team’s international amateur scouting efforts.

Calculating risks was also a key part of Fenstermaker’s undergraduate experience. As Mejdal spent his summers dealing blackjack in-person at casinos, Fenstermaker was a prop online poker player, earning extra money as a student.

“I played about 2,000 hands of poker a week all through college and was relatively successful in doing so,” Fenstermaker said. “That was the foundation of thinking about probabilities, outcomes and associated risks.”

Though Fenstermaker didn’t make it to the majors as a player, he did earn his own championship ring as a member of the Rangers’ championship 2023 season.

Fenstermaker entered a world where analysts were part of baseball teams’ staff. He took multiple roles within the Rangers organization, ignoring recruitment opportunities in other industries like hedge fund management.

“I ultimately said, ‘No, I’m going to stick it through and I’m going to make $50,000 for a couple more years and see if I can’t figure out this baseball thing.’ And I’m glad that I stuck it out and it worked out in the end,” Fenstermaker explained, noting the risks he was personally willing to take to find a career driven by such gambles. “It’s led me to be more objective in terms of how to build the roster while also understanding team dynamics, chemistry, how it all builds a championship caliber roster.”